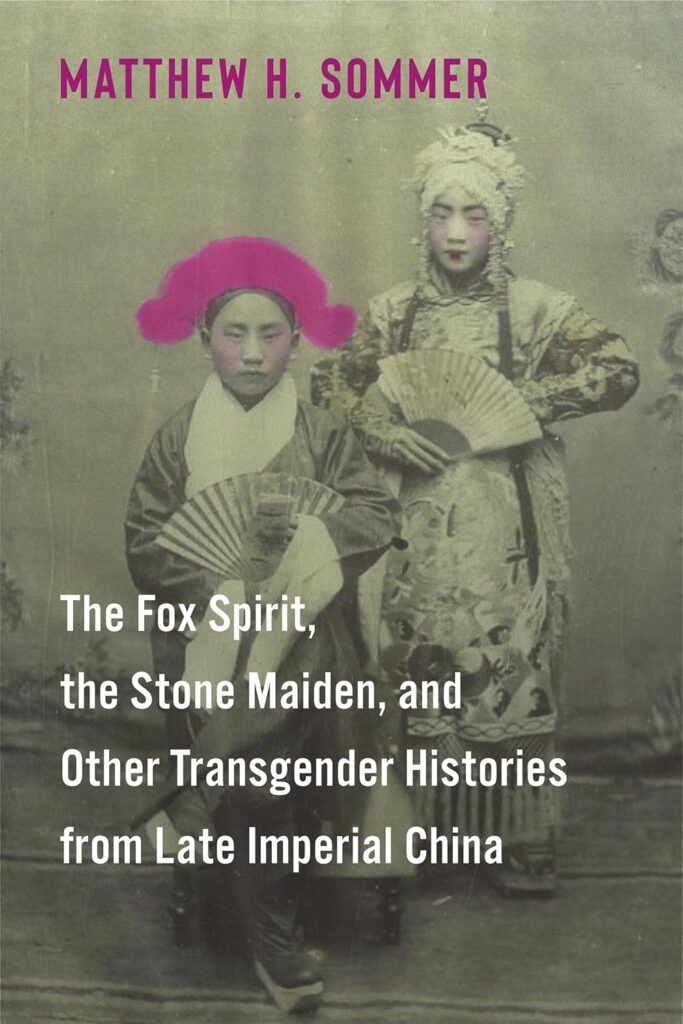

Matthew H. Sommer is a social and legal historian of China in the Qing dynasty (1644-1912). His research focuses on gender, sexuality, and family, and the main source for his work is original legal case records from local and central archives in China. Sommer’s first book, SEX, LAW, AND SOCIETY IN LATE IMPERIAL CHINA (Stanford UP, 2000), was recently published in a Chinese translation (Guangxi Normal UP, 2023) that sold more than 40,000 copies in its first year and was ranked by Douban.com as one of the year’s ten best books in History and Culture. His second book, POLYANDRY AND WIFE-SELLING IN QING DYNASTY CHINA: SURVIVAL STRATEGIES AND JUDICIAL INTERVENTIONS (U of California P, 2015), was the inaugural winner of the American Society for Legal History’s Peter Gonville Stein Award for the best book on non-US legal history in English published in 2014-15. His third book, THE FOX SPIRIT, THE STONE MAIDEN, AND OTHER TRANSGENDER HISTORIES FROM LATE IMPERIAL CHINA (Columbia UP, 2024), won the LGBTQ+ History Association’s John Boswell Prize (co-winner for 2023-24). Future plans include a fourth book, tentatively entitled MALE SAME-SEX RELATIONS AND MASCULINITY IN QING CHINA, and a fifth, CRIMINAL PROCEDURE IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINA: THE QING JUDICIARY IN ACTION.

I had the opportunity to interview Matthew, which you can read below.

First of all, welcome to Geeks OUT! Could you tell us a little about yourself?

I am the Bowman Family Professor of History at Stanford University. As a social and legal historian of Qing dynasty China (1644-1912), my research uses original legal case records from local and central archives to explore gender, sexuality, and family. I am the author of SEX, LAW, AND SOCIETY IN LATE IMPERIAL CHINA (Stanford 2000) and POLYANDRY AND WIFE-SELLING IN QING DYNASTY CHINA (California 2015), which was the inaugural winner of the American Society for Legal History’s Peter Gonville Stein Book Award. My latest book, THE FOX SPIRIT, THE STONE MAIDEN, AND OTHER TRANSGENDER HISTORIES FROM LATE IMPERIAL CHINA (Columbia 2024) won the John Boswell Prize from the LGBTQ+ History Association (co-winner for 2023-24). Future plans include a fourth book, MALE SAME-SEX RELATIONS AND MASCULINITY IN QING CHINA, which I am now completing; and a fifth, CRIMINAL PROCEDURE IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINA.

What can you tell us about your most recent book, The Fox Spirit, the Stone Maiden, and Other Transgender Histories from Late Imperial China? What was the inspiration for this project?

Through a close reading of cases from the Qing dynasty’s (1644-1911) legal archives, complemented by anecdotes from fiction in the genre of “the strange” and late Qing newspaper accounts, this work of social history explores a range of transgender lives and practices in China during the late imperial era. My use of “transgender” derives from Susan Stryker’s practice-based definition: transgender people are those “who move away from the gender they were assigned at birth, people who cross over (trans-) the boundaries constructed by their culture to define and contain their gender.”[1]

Transgender people existed in imperial China. Broadly speaking, we can divide them into two categories. First, there were those who were compelled to trans, notably boy actresses, clergy, and eunuchs, whose vocations required leaving behind normative gender roles based on family and procreation. Many of these people were subjected to coercion, violence, and unfreedom; their gender transing was acceptable and even valorized to the extent that it served the established order of hierarchy and privilege, and did not represent nonconformist self-expression. The second category consisted of people who chose to trans gender, represented in this book by individuals who lived as women despite having been assigned male at birth. When such people came to official attention, they were harshly punished because the only plausible reason Ming-Qing authorities could imagine for “a male to masquerade in female attire” was to penetrate female space in order to seduce or rape the “chaste wives and daughters” cloistered within. (This transphobic scenario closely resembles the modern paranoid fantasy of transwomen as dangerous male predators in disguise who seek to enter female space for some nefarious purpose.) Nevertheless, the fact that our protagonists could live in their communities for years without trouble – often serving as spirit mediums and healers – illustrates the vast gulf separating official and elite ideology from the social realities and mentalities of ordinary people.

The main topic of this book is transgender lives and practices as documented in Qing legal cases. But given the intersectional nature of this topic, my book also makes original contributions to our understanding of law, popular religion, the theater, medicine, and vernacular fiction in the Ming-Qing era.

The inspiration for this book came from the stories of gender transing people that I discovered in legal cases from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century China. I found these stories utterly fascinating and felt it was important to make these people’s lives visible in the present day. This task seems especially vital today, given the current wave of transphobic persecution in the United States and elsewhere, which seems to worsen by the day.

As a scholar, what first drew you to this subject in queer Chinese history?

My older brother (who passed away in 2012 from cancer) was gay, and I was the first person he came out to – that was in 1977, when I was in high school. At that time, the fledgling movement for what was then called Gay Liberation was encountering the first wave of homophobic backlash (Anita Bryant, the Briggs Initiative, etc.). As a teenager growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area with a closeted older brother, I was acutely aware of the political drama unfolding around me.

Later, as I was training to be a social historian of imperial China, I became fascinated by the opportunities to study gender and sexuality as historical topics and to use legal case records to uncover the lives of ordinary people in Qing dynasty China (most of whom were illiterate and left no other records of their lives). I have no doubt that my interest in the politics of sexuality influenced my choice of research topics. Queer history has been a focus for me since graduate school, and my recent book on transgender is a logical outgrowth of my earlier work, even as it took me in new directions.

What are some of your favorite elements of writing and researching? What do you consider some of the most frustrating and/or challenging?

For me, the most exciting stage of any project is the initial phase of research, which involves reading masses of primary sources from late imperial China and using them to try to understand the lives of people from that era. The challenge of studying gender and sexuality as historical topics is that they get at the intersection between what is universal in human experience (because we are all the same species, and diverse as we may be there is a limit to our diversity) and what is specific to particular times and places. In some ways, the past is a very strange place, and yet a focus on gender and sexuality enables one to recognize what we have in common with people living in times and places very different from our own.

As an author who or what would you say are some of your greatest creative influences and/or sources of inspiration in general?

My greatest influences and sources of inspiration as a scholar and writer have been my teachers, many of whom have themselves been historians of extraordinary talent. Their mentorship and the inspiration of their example played a crucial role in my own intellectual formation. I hope to repay them by serving as an effective teacher and mentor for my own students.

Aside from your work, what are some things you would want readers to know about you?

I love traveling, eating good food, drinking good wine and whiskey, spending time with family (including our three cats) and friends, learning foreign languages, reading novels, watching movies, hiking …

What’s a question you haven’t been asked yet but that you wish you were asked (as well as the answer to that question)?

How did you get interested in China?

In October 1978, when I was 17 years old and a senior in high school, I had the (then rare) opportunity to travel to China with my parents as part of a medical professional tour (my parents were physicians, and I was the only minor in the group). That was a crucial moment of transition for China: its post-Mao period of “opening up and reform” was about to begin. That trip changed my life: it felt like I had been living in a two-dimensional world without realizing it, and suddenly the world acquired a third dimension. The following year in college, I started studying Chinese language and taking every course on East Asia I could find – and the rest, as they say, is history.

What advice might you have to give for aspiring writers/scholars out there?

Find a topic you are passionate about! Also, the key to successful writing is to write every day – even if, at the end of the day, you throw out what you’ve written. There are no shortcuts.

Are there any other projects you are working on and at liberty to speak about?

I am currently finishing a book that I’ve been working on (in the background of other projects) for a very long time: its working title is Male Same-Sex Relations and Masculinities in Qing Dynasty China. This book is based on nearly 2000 legal cases that I have collected over many years in the archives in China. I have already written quite a bit about the legal aspect of this topic, so instead this new book will attempt a sort of historical anthropology of male-male sexual acts and relationships.

What specific titles would you recommend for fans of The Fox Spirit, the Stone Maiden, and Other Transgender Histories from Late Imperial China?

For the still very young field of transgender history, I recommend the following two books, which both became “instant classics” when published:

Susan Stryker: Transgender History (Seal 2008); revised edition Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution(Seal 2017)

Jen Manion: Female Husbands: A Trans History (Cambridge 2020)

Neither is about China, but both of these books had a powerful influence on my own recent book.

Finally, what books/authors would you recommend in general to the readers of Geeks OUT?

For queer history, the best starting point is still George Chauncey’s masterpiece, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940 (Basic Books 1994). A wonderful, indispensable book.

Just for fun, I recommend all of William Gibson’s novels, but especially the first: Neuromancer. I also enjoy Patrick O’Brien’s Aubrey/Maturin series of historical novels – beautifully written and often hilarious.

[1] Stryker, Transgender History, Seal Press, 2008: 1.

0 Comments