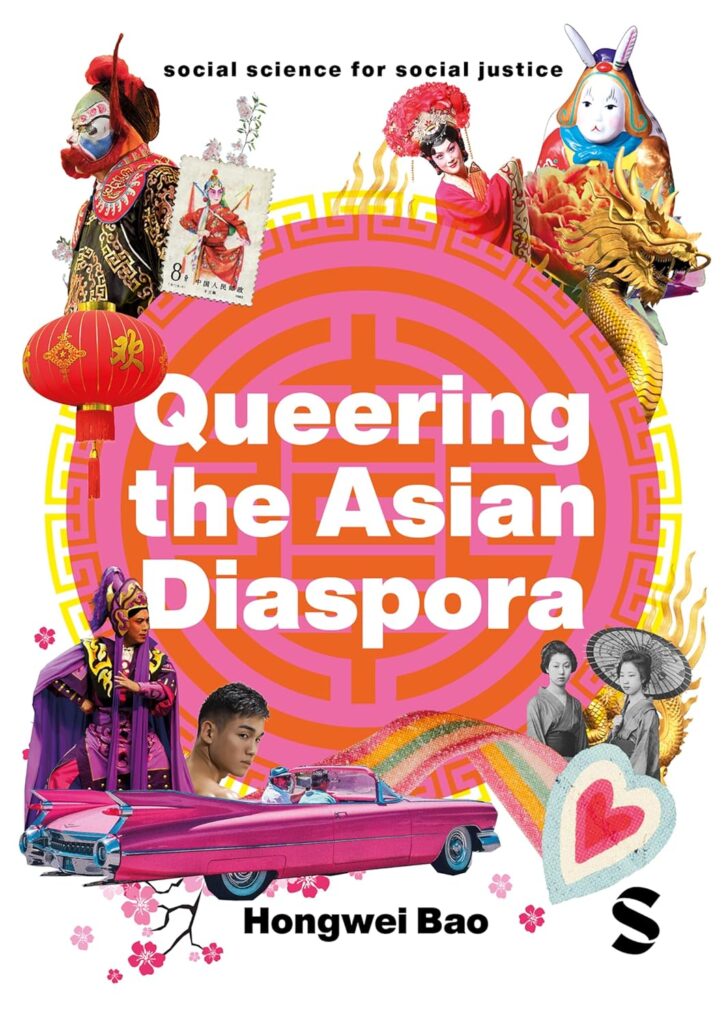

Hongwei Bao (he/him) is a Nottingham-based queer Chinese writer, translator and academic. He is part of the Fifth Word Playwrights, GOBS Spoken Word Collective and Nottingham Playhouse Writers’ Room. He is also a Middle Way Mentee for writing fiction and a New Earth Theatre theatremaker. His work explores queer desire, Asian identity, diasporic positionality and transcultural intimacy. Hongwei is the author of Dream of the Orchid Pavilion (poetry pamphlet, Big White Shed, 2024), The Passion of the Rabbit God (poetry collection, Valley Press, 2024) and Queering the Asian Diaspora (nonfiction, Sage, 2024).

I had the opportunity to interview Hongwei, which you can read below.

First of all, welcome to Geeks OUT! Could you tell us a little about yourself?

Thank you. My pleasure to be here. I’m a queer Chinese writer translator and academic based in the UK. I teach media studies at the University of Nottingham. I am a cultural historian of Chinese queer history in the post-Mao era (1978 to present). Meanwhile, I am a poet, fiction writer and playwright. I have published two poetry books (The Passion of the Rabbit God and Dream of the Orchid Pavilion). I also translate between Chinese and English, and have been introducing queer Chinese poet Mu Cao’s works to an Anglophone readership. All my scholarly and creative work focus on queer Chinese identity and migration experience. I see them as an organic and holistic body of work. My scholarly work offers research and theorisation for my creative writing; and my creative writing serves as a translation of my scholarly work to a broader readership.

What can you tell us about your most recent project, Queering the Asian Diaspora? What was the inspiration for the book?

Queering the Asian Diaspora (Sage, 2024) is a book about queer Asian identity and diasporic experience, especially since the COVID pandemic. The COVID pandemic hit the Asian communities particularly hard: many Asian people experienced Sinophobia and anti-Asian racism. Meanwhile, there was also a surge of Asian community activism worldwide, represented by the #stopasianhate movement. In the Asian communities over the last decade, there have been a lot of discussions on Asian identity, heritage and values, some of which risk reproducing essentialist, nationalist, patriarchal and heteronormative discourses. For example, the notion of ‘family’ is often seen as an intrinsically good thing and the respect for the elderly is seen as an unproblematic virtue. As a queer person, I feel that a queer and intersectional perspective is largely missing the discussion. At the same time, queer Asians have been marginalised in the broader LGBTQIA+ social movements, which is predominantly white. Notions such as ‘coming out’ are seen as a must-do for queer people; failure to do so is seen as lacking in courage and authenticity. Yet for many queer Asians, coming out may not always be the best choice; and not coming out may end up being an ethical choice. So Queering the Asian Diaspora is my effort to insert queer Asian perspectives into the picture, demonstrating queer Asians have a lot to contribute to Asian community activism as well as LGBTQIA+ social movements.

Queering the Asian Diaspora was the direct outcome of the COVID pandemic. While I have been affected by anti-Asian racism, I have also been inspired by countless queer Asian artists, activists and community organisers. The book also serves as an incomplete documentation of their work between 2020 and 2023. The 156-page small book is necessarily selective, incomplete, limited by my own knowledge and experience. For example, the book primarily focuses on East and Southeast Asian communities in Europe, with which I have direct contact. The book has a strong ‘art’ focus, which reflects my interest as a cultural historian. I see the book more as a point of departure than a conclusion. It joins other authors and books in charting the development of Asian identity and activism globally in a long historical process. If Asian identity is traditionally understood geographically, associated with specific geocultural imaginaries, and queerness as a sexual identity, what we see today is the multiplication, diversification and intersection of both identities. The book is thus a celebration of hybridisation of identities, cultures and politics, resisting essentialist claims, nationalist co-option, and neoliberal capture.

As a scholar, what drew you to the art of writing?

Writing for me is a way of self-expression. When I was a child, I was extremely shy and introverted. A school teacher even suspected that I had a speech impediment. I retreated to reading and writing; it was the only thing I could use to express myself. I wrote many essays and poems. An essay I wrote got a national prize for young people’s writing. I even started writing a novel and had to give up after the first fifty pages – I was not ready to write about the adult world as a secondary school student; my experience was too limited.

I attended a top School of Journalism and Communication in China. I believed that journalism could help expose social problems and help amplify marginalised voices in society, until my dream was crashed by the reality: China’s media censorship meant that journalists cannot write the way they want to.

Then I embarked on a PhD at the University of Sydney in Australia. I decided to write a history of Chinese queer culture and activism in the post-Mao era, which was seriously under-researched at the time. I thought: since I had four years’ time for reading and writing, I would be in a good position to do the job. I seriously underestimated the scope of the task. Little had I expected that twenty years later, I am still working in the research area!

In recent years, especially since the COVID pandemic, I have started to pick up my childhood dream to be a writer. I write poetry, fiction and stage plays. Creative writing gives me a way to deal with work pressure and everyday anxiety. It forces me to look inside myself and reflect on my own experience as queer, Chinese and migrant, the same topics I deal with in my scholarly work albeit in a different form. I find my creative writing and academic writing mutually fertilizing; they help me explore the same topics from different perspectives.

An aspect worth mentioning is that while I wrote mostly in Chinese when I lived in China, I have written predominantly in English since my PhD years. I did not grow up speaking English. Writing in a learned, second and foreign language has its own perks and challenges. Over the years, I have come to accept the fact that I will never be able to write well like a native speaker, and that is OK. Writing helps me express my ideas, and it has done the job so far, so I am happy.

How would you describe your creative process?

I’m a spontaneous writer. I’m often inspired by the books I have read, films I have watched, people I have met, or events I have attended. Sometimes an idea come to me and I have to jot things down – even if it’s just a few words. I carry pen and paper with me most of the time, which sounds very old-fashioned. I then sit down when I have time to find the right form for the idea. This is why I write a lot of short and work-in-progress pieces: book reviews, film/exhibition reviews, in conversations, translations, op-eds, blog entries, poems and critical essays. Every now and then, I would look back at these fragmented pieces of writing to figure out the bigger picture. This is how most of my books come about.

I also work well with deadlines, despite my frequent complaints about them and inability to meet many of them. I like attending writing workshops where the workshop coordinators give a topic and a timeframe, then everyone starts writing. Many of my poems have been written in the workshops. I’m often able to write a draft poem in a workshop and then go back home and type it out. I then edit it until they are ready for sharing. Because the writing prompts are unpredictable, I have written some poems that I wouldn’t usually write and that surprised myself too.

What are some of your favorite elements of writing? What do you consider some of the most frustrating and/or challenging?

My favorite element of writing is the process of writing itself: inspired by an idea that excites me and trying to put the idea down in words. This process is not always easy or straightforward: but being eventually able to find a way to do so is an extremely fulfilling experience. When I write, I retreat into the world of my writing, and forget about everything else. It gives me a great sense of autonomy in a world where we have very little control of so many other things. So writing entails the forgetting of oneself and the world, and the making of new ones. I guess this is what drew me to writing in the first place.

One of the most challenging things for me is to face critiques, especially from myself. As a scholar, I’m used to being critical about things, and this is fine when it comes to academic and critical modes of writing. But when writing poetry, fiction and stage plays, my inner critical voice may become an impediment to my creative process and I need to shut it down, at least for the first draft. This is not always easy. In the second and later drafts, these critical voices will prove useful in making my arguments clearer and more balanced. My workshopping and peer review experiences have made me more receptive to constructive criticism, and my work becomes stronger as a result of these critiques.

Another challenging thing for me is to overcome imposter syndrome. Despite having authored five scholarly monographs and two poetry books, I still feel like an imposter as an academic and a writer. I find this a common experience amongst queer and global majority writers. The benchmarks for ‘success’ and ‘good books’ are often set by other people or industry matrices. We need to reverse the narrative and believe in the power of our own words for our communities and society.

As a writer, who or what would you say are some of your greatest creative influences and/or sources of inspiration in general?

I’m an avid reader, and read extensively since childhood. I’m a fan of Tolstoy and Flaubert in my youth. Now my time is limited. I focus my reading primarily on queer literature and Asian literature, and their intersections. My queer fiction influences include James Baldwinm, E. M. Forster, Alan Hollingurst, Adam Mars-Jones and Christos Tsiolkas, and my queer poetry influences include Robert Hambeger, Maria Jastrzębska, John McCullough and Gregory Woods. My (mostly queer) Asian literary influences include Mary Jean Chan, Chen Chen, Elaine Chiew and Ocean Vuong, among others.

I know I haven’t said much about Chinese writers – this may appear very odd as someone growing up in China and spending my formative years writing in Chinese. I was a rebellious person in my youth and did not want to read anything from China’s literary establishment. As I get older, I have started to appreciate Chinese literature for its richness and diversity. I love classical Chinese poetry and prose, and learned many of them by heart when I was a child (partly thanks to China’s education system which encourages memorisation); but I cannot imagine myself writing in that style. In recent years, I have started rewriting classical Chinese stories (such as Chang’e, Qu Yuan, the Rabbit God and Mulan) in contemporary poetic forms, giving them a feminist and queer twist. I also like contemporary (and often underground and grassroots) Chinese poetry as I read more of them and get to know more poets through my poetry scholar friend Maghiel van Crevel. I am grateful to have the opportunity to read the works by Chinese writers writing outside China’s literary establishment such as the queer Chinese poet Mu Cao whose works I’m translating. In this way, I am reconnecting to Chinese literature.

What advice might you have to give for aspiring writers/scholars out there?

Especially for writers from marginalized communities including queer writers and Asian writers, your voice matters and it deserves to be heard by more people. There are so many obstacles in your life, such as the lack of opportunities and access, a perpetual imposter syndrome, and a competitive market-driven publishing industry, don’t let them stop you from writing and don’t give up writing. If you have a story that you would like to read but haven’t seen it written, you are the one to write it.

For aspiring scholars, writing matters. The academia is full of books and articles that use abstruse language, which is not meant for a general readership. That’s fine but don’t let this scare you, or make you think it’s the only legitimate academic language. Clarity should be the top priority. One does not need big words and complex syntax to express ideas. Academic writing can be reader-friendly and stylistically beautiful too. This advice is particularly relevant for early career researchers and researchers who write in English as a non-native language.

Are there any other projects you are working on and at liberty to speak about?

My second poetry collection, Self-Portrait as a Banana, was published by Poetic Edge Publishing on 20 September 2025. The collection is a meditation of my own queer and Asian diasporic identity, using, appropriating and subverting old-fashioned tropes such as rice (Asian), banana (an Asian person born or living in the West), Chinese gooseberry (also known as a kiwifruit) and beckoning cat (aka waving cat). It’s a bold (and some say outrageous), funny and uplifting book. You can get the book on Amazon or other online bookshops.

Finally, what LGBTQ+ and or Asian diaspora books/authors would you recommend to the readers of Geeks OUT?

In terms of fiction, I have recently read Alan Hollinghurst’s novel Our Evenings, Jiaming Tang’s novel Cinema Love, and Byan Washinghton’s novel Memorial. Our Evenings is a story of growing up gay as British Burmese in the UK. Cinema Love is a story centering on the lives of women and gay men in Asian American migration. Memorial is a queer love story between a Japanese American and African American. Elaine Chiew’s novel The Light Between Us and Ge Yan’s short story collection Elsewhere are pretty exciting too. I can recommend them.

In terms of nonfiction, I have been drawn to life writing in recent years, such as Jeremy Atherton Lin’s autobiography Deep House and Curtis Chin’s memoir Everything I learned, I Learned in a Chinese restaurant. The former is a story of a gay couple’s pursuit of true love and same-sex marriage across national borders, and the latter is a coming of age story growing up gay and Chinese in Detroit’s Chinatown in the 1980s.

In terms of poetry, Mary Jean Chan’s poetry collection Bright Fear is a wonderful collection of poems depicting Asian diasporic experience during the pandemic. Robert Hamberger’s new collection Nude Against A Rock is a bold celebration of queer life and love and has the perfect combination of emotional intensity and linguistic precision.

0 Comments