Trung Le Capecchi-Nguyen (Trung Le Nguyen, professionally) is a Vietnamese-American comic book artist and writer from Minnesota. He was born in a refugee camp somewhere in the Philippine province of Palawan.

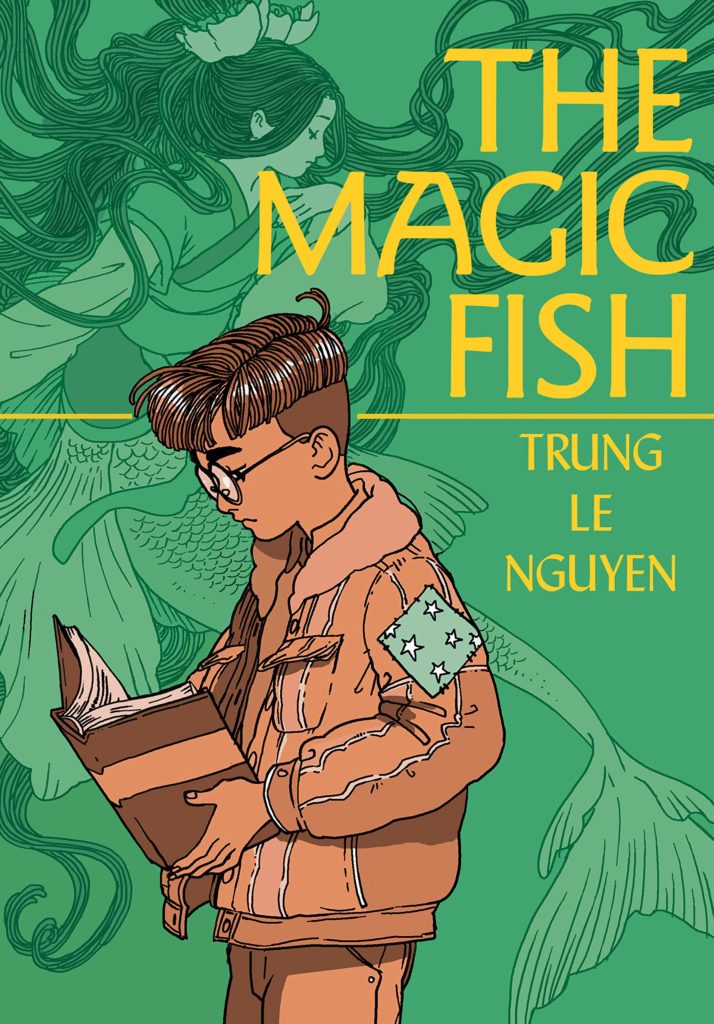

Trung’s first original graphic novel, The Magic Fish, was published on October 13th, 2020 through Random House Graphic, an imprint of Penguin Random House. It won two Harvey Awards. Trung has also contributed work for DC Comics, Oni Press, Boom! Studios, and Image Comics.

He currently lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota and raises three very spoiled hens. He is fond of fairy tales, kids’ cartoons, and rom-coms of all stripes.

I had the opportunity to interview Trung, which you can read below.

First of all, what first drew you to storytelling? At what point did you realize you wanted to tell your own stories?

I consider my relationship to storytelling-on-purpose somewhat new. I think everybody figures out the ways they best like to express themselves in their daily lives, and being a career creative person formalizes that a little bit. The Magic Fish is the first work of fiction I’ve ever really done, so I’m still sussing out my relationship to storytelling, honestly.

How would you describe your crafting style? How do you go about creating on a continual basis while balancing day-to-day life or stresses?

My work style is so chaotic, in part because of its newness and in part because I’m a very scattered sort of person. My work-life balance is largely fine by luck because I have a loving support network behind me, and my collaborators are smart, experienced people who remind me to take days off and give myself more room to recover. I was an overcommitted, high-achieving kid who grew up into an overworked and frequently burned-out adult, and I’m still figuring out how to live with it and work around it.

As far as the more granular details in making comics, I like regimented segments. I start with an outline, then I write the script, then draw thumbnails, then draw the pages. I had assumed I was a visually oriented person who would prefer to start with the thumbnails and also make the script at the same time. I was shocked to discover that I actually need a script to work from. I like that level of organization, and from there I feel like I waste less time and wrist strain drawing and redrawing concepts.

In your narratives, language seems to stand as something that can divide people while stories stand for something that connects? Do you agree with that assessment?

If a reader tells me that’s their takeaway and that it feels true to their life, then yes, their assessment is correct. For me, language is a tool. It’s not precisely the thing that divides, though it can certainly feel like that, but the characters figure out a way to identify the gaps in their languages and bridge them in whatever ways they can. Sometimes it’s switching back and forth between two languages, and sometimes it’s speaking a hybrid language specific to their home, as with a lot of immigrant families.

That sort of language use, cobbling things together to build contexts that convey specific ideas, is very organic. By my estimation, the instances where language becomes a divider is when it’s coupled with systemic forces. So when a hybrid-language speaker in the United States is regarded as unintelligent, for example, because they don’t test well or something, there are a lot of interlocking systems at play upholding that unfair assessment. That’s not the fault of language. Language is organic and flexible. It’s not a sedentary, calcified artifact. Language is meant to shift as its users shift. We could have a rudimentary understanding of a language and still go about our day beyond the ken of the formalities of pedantic grammarian navel-gazing. We all do it. We live among and around people who speak different languages.

Storytelling becomes an extension of that language use, so I don’t find it useful to create a binary where language is the divider and storytelling is the connector. The loss of language, the angst of diasporic identities, and the feeling of bereavement of a space and culture, all that can be chalked up to imperialism and war in this instance.

In The Magic Fish, you explore a narrative in which a mother and son, dealing with generational and multicultural gaps, connect through the fairytales they read together. As someone whose often only shared literary references to her own parents were fairy tales, why do you think this medium has such extensive potential?

I think, very simply, fairy tales are frequently some of our earliest experiences with storytelling, and they also happen to be very old. This seems to uniquely position it as almost a narrative control group, and the stories your parents hear and the stories told to you can be a neat little generational bridge. And because they’re oral tradition, because they survive in iterations and retellings, they have this beautiful elastic quality that makes them so accessible. I think that’s why I center them in my storytelling. I love the imperfect ways people recollect fairy tales. Most of us could recount the tale of Cinderella, and the pieces we emphasize and the ways the characters look and sound might all be different, but the fairy tale lends itself to being a vehicle of participation where everyone gets to storytell. “I know this part,” or “I love this part!” or “Wow, I remember that!” It’s a little silly, but it’s a little like that feeling you get at a club when a beloved song comes on and the whole dance floor lip syncs along! It’s that feeling, but small and intimate. I love that.

One of the many things that touched me about Tiến’s struggle with coming-out was that he did not have the language to describe the queerness to his Vietnamese family. As someone who had similar struggles in regards to finding language (Russian in my case) to describe queer identity growing up, what do you feel is the connection between language and identity?

I mentioned before that language is a mutable tool, so I don’t think there’s an essential connection between language and identity. It’s part of the makeup of a culture, so certainly the verbiage we find will have an effect on how we employ language to describe, for instance, queerness. Language can come with baggage over long use, and words can become tarnished and feel barbed. Parts of it can be discarded or it can be reclaimed and rehabilitated into use. Language seems to have a difficult time keeping up with identity, actually. And even when it seems to catch up, it’s only temporary. The culture moves on, and new language needs to be made or old language comes back into fashion. My best guess is just that language is not compatible with essentialism because language is slower than identity. Sometimes it takes a little while for language to wrap itself around something everybody was already living with.

While reading your book, one of the things that stood out to me was how you explored The Little Mermaid as an immigrant narrative in addition to a queer one? As a fairytale created and shaped in such a different century than today, why do you think this story continues to hold so much relevance and so many meanings?

Honestly, I’m sure every reader has their different reasons. I can say that Andersen’s Little Mermaid was a personally resonant story for him in particular. It was written as a literary fairy tale for children by an author who was known in his day, and that’s a meaningful distinction from other stories we popularly think of as fairy tales. Andersen’s stories are different from Perrault’s or the Grimm stories because they don’t pretend they don’t have a point of view. The Grimms collected their stories from all over, but they edited them and increasingly sanitized them as newer editions were published. And certainly, The Little Mermaid had its forebears in Rusalka and Ondine, but Andersen was writing a story from his own heart and from his own point of view, first and foremost. He was not immune from an editorial process, and the story was affixed with this weird epilogue about the little mermaid earning a human soul through endless suffering at the whims of children all over the world. But the heart of the story, the special yearning and the toilsome sacrifices upon which Andersen’s story leans, remains deeply personal, and I think people respond to that.

In The Magic Fish you explore three distinct and beautiful fairytales. Were there any other stories you considered including in your graphic novel? Are there are other fairytales you would still like to explore in your work now?

At one point I wanted to include the Japanese fairy tale of the fisherman and the turtle princess to express that Rip Van Winkle effect that Helen feels when she finally comes back to Vietnam and finds everything unrecognizable. There just wasn’t enough room to do it, ultimately, and I thought three basic fairy tales made for a pleasing number.

Aside from making comics, what are some things you would want readers to know about you?

There’s not too much to tell. I love old sitcoms, and I have them on in the background while I draw. I play a lot of video games, though I get overly competitive and yell at the screen a lot. I really like desserts! I have three very sweet hens named Beatrice, Paulette, and Edwina. I watch all the main Rankin Bass holiday cartoons every year around Christmas.

As a creator, what advice would you give for other creators who are looking to explore identity in their craft?

My main advice for creators, especially creators who come from marginalized backgrounds, is that they should protect themselves from the pressure to get everything right all the time. We all change and grow, and even the stories we tell about ourselves won’t always well represent us in time. I want everyone to be free of the burden of being the sole representation, and that can be accomplished by getting as many diverse voices published as possible. When we know there are others like us in the room, the weight of carrying the entire arc of our stories is lightened. We can be free to tell the narrowly specific, messy, and fun stories of our hearts instead of feeling any special responsibility of edifying an ignorant readership.

Are there any projects you are working on right now and at liberty to speak about?

I am working on my second OGN for Random House Graphic at the moment. I’m very excited about it. It doesn’t have a solid title yet, but I am loving the process of writing it so far. I can’t wait for everyone to meet these new characters!

Finally, what books (both LGBTQ+ and otherwise) would you recommend to the readers of Geeks OUT?

I love just about anything by Jeanette Winterson. Her writing is absolutely incredible. I recommend The Daylight Gate and also Lighthousekeeping. MariNaomi’s books are all formative graphic storytelling for me. I read Dragon’s Breath and Turning Japanese back to back before I thought I would ever make graphic novels, and they blew me away. I loved No Ivy League by Hazel Newlevant, and Flamer by Mike Curato absolutely gutted me. I’m currently working my way through Cemetery Boys by Aiden Thomas, and the whole thing just makes me giddy with joy. This was the sort of book Teen Me would have loved to bits and carried on into forever. I’m sure there’s more, but those are the ones that spring to mind right away.

0 Comments