YILIN WANG 王艺霖 (she/they) is a writer, a poet, and Chinese-English translator. Her writing has appeared in Clarkesworld, Fantasy Magazine, The Malahat Review, Grain, CV2, The Ex-Puritan, The Toronto Star, The Tyee, Words Without Borders, and elsewhere. She is the editor and translator of The Lantern and Night Moths (Invisible Publishing, 2024). Her translations have also appeared in POETRY, Guernica, Room, Asymptote, Samovar, The Common, LA Review of Books’ “China Channel,” and the anthology The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories (TorDotCom 2022). She has won the Foster Poetry Prize, received an Honorable Mention in the poetry category of Canada’s National Magazine Award, been longlisted for the CBC Poetry Prize, and been a finalist for an Aurora Award. Yilin has an MFA in Creative Writing from UBC and is a graduate of the 2021 Clarion West Writers Workshop.

I had the opportunity to interview Yilin, which you read below.

First of all, welcome back to Geeks OUT! Could you tell us a little about yourself?

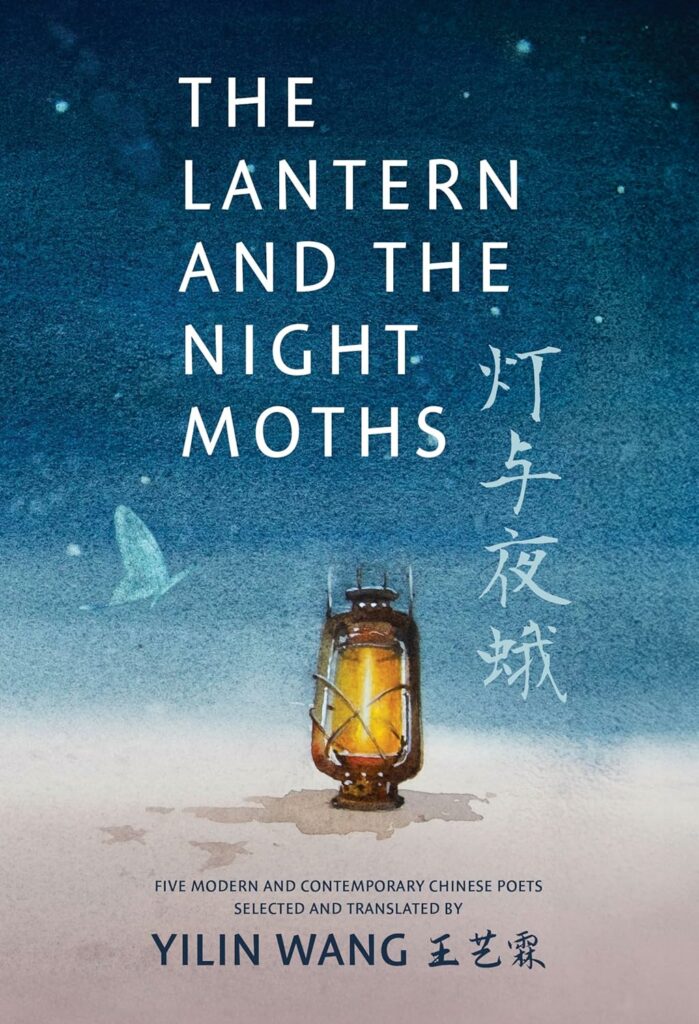

Hello! Thank you so much for having me. I’m a queer Chinese diaspora writer, poet, literary translator, and editor living on the stolen and occupied lands of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-waututh nations (known colonially as Vancouver, Canada). I’m a genderqueer femme who is biromantic, demiromantic, and asexual. My book The Lantern and the Night Moths is forthcoming with Invisible Publishing available now.

What can you tell us about your upcoming book, The Lantern and the Night Moths: Five Modern and Contemporary Chinese Poets in Translation? What inspired this project?

The Lantern and the Night Moths 灯与夜蛾 is my debut book. It contains a selection of poems by five modern and contemporary Chinese poets whose work collectively span the past century. Each poet’s work is accompanied by a short essay that I wrote, where I delve into what their work means to me personally, the translation process, and any literary, cultural, or sociopolitical contexts.

I first started translating Chinese poetry around six years ago, in a creative writing workshop during my MFA program, when I became frustrated that many of the stories and poems being studied in English and creative writing programs tend to be very Eurocentric in form and content. I started deliberately seeking out more Chinese literature to read—both in Mandarin and in translation.

While I found many translations of classical Chinese poetry, especially translations of poems written in the Tang dynasty, many of the collections are completed by Sinologists for niche, academic readerships. Others are often full of outdated, orientalist, and exoticizing language. For Chinese poetry in particular, there are even numerous “bridge translations”–translations where a writer who couldn’t actually read the original text simply adapted and rewrote a “literal translation,” presenting their own imagined version of a Chinese poem, without sensitivity for the original text’s emotional nuance, stylistic features, and surrounding context.

Frustrated by this phenomenon and the underrepresentation of BIPOC heritage speaker translators, I drew on my skills as a poet and my multilingual background to start translating classical and modern Chinese poetry. I eventually decided to create an anthology that could serve as an accessible introduction to modern Sinophone poetry, aimed especially at members of the Sino diaspora, fellow writers and translators, and general readers interested in Chinese literature.

Regarding the five poets chosen for this project, what drew you to these specific names?

I have chosen the work of five poets who I each consider to be a literary zhīyīn 知音. The first poet included in the anthology, China’s first modern feminist poet, Qiu Jin 秋瑾, wrote frequently about her own longing for a zhīyīn. A zhīyīn literally means “someone who understands your music” or “someone who understands your songs.” The word is used to describe a close friend, a kindred spirit with shared ideals, a queerplatonic soulmate.

When I translate Qiu Jin’s work—and the work of the other poets I have chosen for the anthology—I feel like I am in conversation with fellow zhīyīn. While each poet has their own interests and styles, I see their work collectively as a series of ars poeticas on the art of modern poetry in Chinese. Through the anthology, I hope to introduce readers to a wide range of voices, from the feminist poet Qiu Jin 秋瑾 (who wrote at the end of the Qing dynasty) to the celebrated modernist poets Fei Ming 废名 and Dai Wangshu 戴望舒 (who wrote in the first half of the 20th century) to the talented contemporary poets Zhang Qiaohui 张巧慧 and Xiao Xi 小西.

Out of all five poets included, I especially have a soft spot in my heart for Qiu Jin’s poetry. As a genderqueer femme, I connect deeply with her words that reflected on women’s friendships and cross-dressing, subverted heteronormative views on relationships and marriage, and advocated tirelessly for gender equality. Folks interested in listening to me discuss her work can check out this podcast interview with The Ace Couple.

Translating is often described as an art and a science. How would you tend to describe it and your own relationship to the work of translating?

In the book, I try to foreground the invisible labour that translators do, work that is often overlooked and underappreciated. The first translator’s essay is written in the form of a letter addressed to the poet Qiu Jin. A letter is a very personal, intimate form of writing. I chose the format because I see translation as a dialogue, unfolding between the translator and the poet, between the source text and the target language, between the translation and its readers.

In another essay, I also discuss that while the art of writing is often compared to pregnancy and childbirth, the work of a translator is closer to that of a maternity nurse. “How does one go about bringing a literary text, so tender with warmth, vulnerabilities, and lyricism, into a distant, unfamiliar world that it might not be ready to encounter? I must guide it with gentle hands to ensure its spirit is kept alive and intact during this transformative, and often excruciating process.”

The book includes five essays on translation in total, where I share my personal journey as a translator, reflections on the process, anecdotes about the poets, and historical and sociopolitical contexts. I’m always curious about the creative practices of other poets and translators, so I hope these essays can be interesting and informative to others in a similar way.

In your bio, it states that you are “a big fan of wǔxiá and xiānxiá fiction, historical c-dramas, Classical Chinese poetry, and East Asian storytelling and narrative structures.” If you wouldn’t mind, I would love to hear any of those stories that you would consider to be some of your personal favorites?

I wrote a primer on wǔxiá fiction for SFWA’s bulletin before for folks who are not familiar with the genre. I always recommend folks to read Jin Yong’s Legend of Condor Heroes 射雕英雄传, which I consider to be a classic in the genre. I also enjoyed the 2017 c-drama adaptation of the same series. Some other favourite xiānxiá dramas include Journey of Flower 花千骨, Love Between Fairy and Devil 苍兰诀, and Once Upon a Time in Lingjian Mountain 从前有座灵剑山.

For folks who want to learn more about Chinese narrative structures, I strongly recommend Ming Dong Gu’s Chinese Theories of Fiction; it’s an academic book and fairly dense, but really insightful. It does an exceptional job providing a framework for thinking about Chinese narratives and story structures.

I would absolutely recommend The Lantern and the Night Moths to readers and audiences who are interested in c-dramas and Chinese media in general, because I consider poetry to be inseparable from Chinese popular culture. Many dramas regularly quote and allude to poems full of idioms and allusions, and understanding the poetry can really help audiences better appreciate Chinese dramas and films. While my book focuses on modern poetry, the poems do build on and engage with the classical poetry tradition, and folks interested in that can check out this bingo card that I created a while back to introduce folks to common tropes in Classical Chinese poetry.

As a creative, who or what would you say are some of your greatest creative influences and/or sources of inspiration in general?

I have so many influences, but I am a huge fan of Ken Liu’s work, both as a writer and translator. I love Gillian Sze’s book Quiet Night Think, which I re-read while working on this anthology. I also really enjoying reading a wide range of nonfiction on the art of translation; when I was fighting the British Museum over their misuse of my translations without permission, I drew strength and inspiration from the chapbooks Say Translation is Art by Sawako Nakayasu and Notes on Mother Tongues by Mirene Arsanios.

Are there any other projects you are working on and at liberty to speak about?

I’m currently working on translating a full-length collection of Qiu Jin’s poetry. She wrote over two hundred poems during the thirty-one years of her life, and I’d like to translate a selection of her most representative and powerful poems to share them with more readers. I’m also working on a collection of my own poems about multilingualism, translation, and Sino diaspora experiences.

Finally, what LGBTQ+ books/authors would you recommend to the readers of Geeks OUT?

Some poetry books written in English I’d recommend are Isabella Wang’s Pebble Swing, Grace Lau’s The Language We Were Never Taught to Speak, Larissa Lai’s Iron Goddess of Mercy, and Mary Jean Chan’s Flèche. For readers who understand Mandarin, I recommend

同在一個屋簷下:同志詩選, an anthology of queer Taiwanese poetry.

Header Photo Credit Divya Kaur

0 Comments