Kyo Maclear is a critically acclaimed author whose books have received starred reviews, appeared on numerous “Best of” lists, and been published in multiple languages around the world. One of her picture books, Virginia Wolf, has been adapted for the stage, and another, Julia, Child, is currently being adapted into an animated television series.

Gracey Zhang is a freelance illustrator and animator. She graduated with her BFA in Illustration from the Rhode Island School of Design. Her first author-illustrator picture book, Lala’s Words, will be published in 2021 by Scholastic.

I had the opportunity to interview both Kyo and Gracey which you can read below.

First of all, welcome to Geeks OUT! Could you tell us a little about yourselves?

KM: Thanks so much for inviting us. I’m Kyo and I live in Toronto (Tkaranto) where I write books for big and little people, across genres.

GZ: Hello! My name is Gracey Zhang and I’m an illustrator, originally hailing from Vancouver, Canada and am now based in New York.

How did THE BIG BATH HOUSE come to be? Where did the inspiration for this story come from?

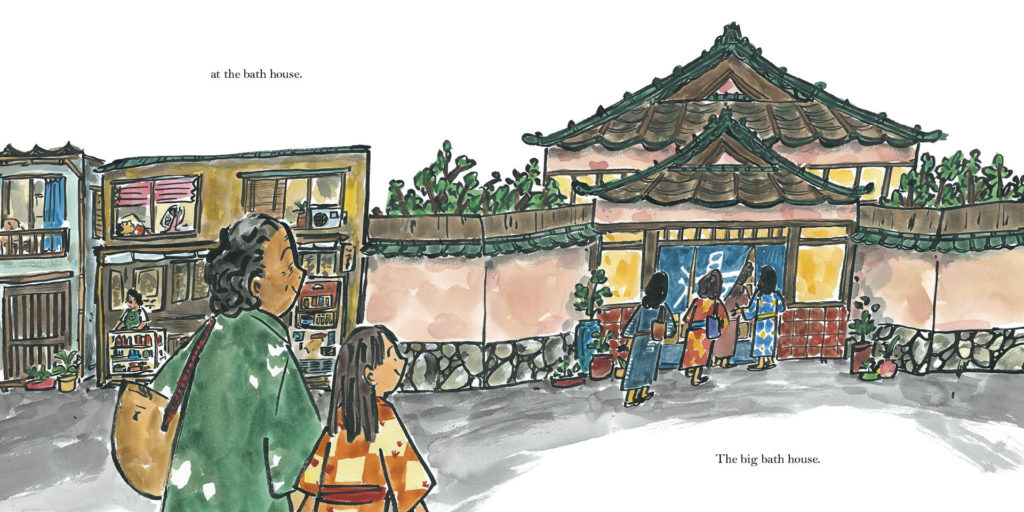

KM: The story came from childhood memories of hanging out with my Japanese family in Tokyo. There were lots of aunties, cousins and an incredibly strong and kind obachan (grandmother) whom I adored. Every visit would begin with a trip to the local sentō (bath house) where we would disrobe and catch up. I wanted to share this magical matriarchal world with kids.

GZ: I was passed along the manuscript for THE BIG BATH HOUSE and fell in love with it immediately. My mother had spent her university and young adult life in Tokyo, Japan so she often brought me there when I was younger to revisit her friends and life there. I remember a memorable trip to a bath house with my mother, younger sister, and a family friend. It was such a nice change to openly soak in the nude without embarrassment, something that wasn’t readily available growing up in a small town in Canada.

How did you each get your start in children’s literature? Do you remember any stories that resonated with you growing up?

KM: I wrote my first kid’s story as a chapbook. It was stapled paper in an edition of 30 copies. It was called “Spork” and I created it with my partner for friends and family to celebrate the birth of our first child. Spork is a hybrid—part spoon, part fork—and imagines a multi-cutlery world. It’s a parable about the limits of categories and it eventually became a published picture book, illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault. So, my entry into the world of kidslit was unplanned but, looking back, it makes so much sense. I’ve always loved visual storytelling. My faves as a child included the Peanuts and the Moomin stories. I love Charles Schultz for the small but profound way he captures big existential questions. And I love Tove Jansson for her trippy world of protean creatures who are always willing to extend a welcoming hand.

GZ: I recently published my first book last summer, while working on it I also had the opportunity to illustrate the stories of so many amazing authors. It’s been exciting to see them being put out in the coming months!

One of your previous books, the graphic novel Operatic, discusses queerness with a gentleness I really appreciated (and an element that seems to permeate throughout your work.) Could you discuss some of the inspiration and craft process behind that book?

KM: Thank you. That’s nice to hear. Operatic was sparked by my sons’ middle school music teacher. He ran the LGBTQ+ lunch club and rock band club and created a canopy for a lot of students who were coming out and/or transitioning. He also introduced my sons to a broad history of music.

I knew I wanted opera to be a theme in this book because I think it stokes such strong reactions in people. As someone who generally tends to veer toward the spare and lo-fi, I used to find opera over-the-top. The performances seemed almost laughable, like badly acted musicals with people shouting into each others’ faces simultaneously. But my partner loves opera and over time the form’s strangeness and unlikeliness has receded. What I like about opera is how it gets to emotional essence and deep feelings as quickly as possible. Wayne Koestenbaum has been so brilliant at capturing the affinity between gay men and opera and celebrating the oversize, lavish, ‘too-muchness’ of the genre. So, anyway, opera seemed a perfect backdrop for a story set in middle school where passionate emotions are the norm, where days are mini epics. Opera is basically social realism—I mean, who at age 13 or 14 doesn’t kind of feel like dropping to one knee and announcing a crush in a yelly voice?

The character of Maria Callas intrigued me because she did not have a conventionally beautiful voice. The Callas voice was considered too melodramatic, too imperfect, even “too manly”. She was thought to wobble on her high notes. I thought she was a great figure to think about what it means to be ‘flawed’ or ‘too much.’ I’ve always been drawn to historical figures who test boundaries and who can’t be tamed into easily acceptable categories.

I worked with an illustrator, Byron Eggenschwiler, who did a great job translating music into a visual language. We also knew the story would not resolve in a traditional way with a couple riding off into the sunset. It ends with an ensemble of characters to celebrate the power of friendship.

Having read previous interviews, it seems like this project is personal to you both in similar ways. Mind you discussing that a bit?

KM: The story came from childhood memories but I chose to use second person narration to immediately steep the reader in the experience and, hopefully, get away from a touristy lens that might see the bathhouse as ‘other’ or ‘exotic.’ I wrote it with diasporic, immigrant, Asian communities in mind because I think a lot of kids have shared a similar experience of bonding with family despite barriers of language and distance. I also wrote it for my mum, who has been dealing with illness.

GZ: There’s such a strong difference in the way nudity is treated in the two cultures I grew up in. I remember seeing how many Asian aunties navigated the showers at pools in Canada and how differently it contrasted with peers of mine who grew up in Canada. As a child, it was pointed out to me by a classmate who thought the openness of nudity should be something to be hidden behind changing rooms. It was an observation I hadn’t thought too deeply of at the time, especially as a teenager who kept her swimsuit on religiously while showering and changing at the pools in Canada. Though now I’m quietly delighted when I’m at the YMCA and see New Yorkers of all ages and origins walking and talking in the nude.

When it comes to body positivity in children’s literature, it seems we’re still at an impasse in the West when books like Maurice Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen keep getting banned for showcasing nudity. How did it feel touching this subject directly in your book?

KM: Sigh. I know. Why the impasse? Why this weird puritanism? I recently blurbed a graphic memoir called My Body in Pieces by Marie-Noëlle Hébert that delves into body image issues and what really struck me about it was how seldom I see work that represents different body types, let alone work that openly addresses the violence of fatphobia.

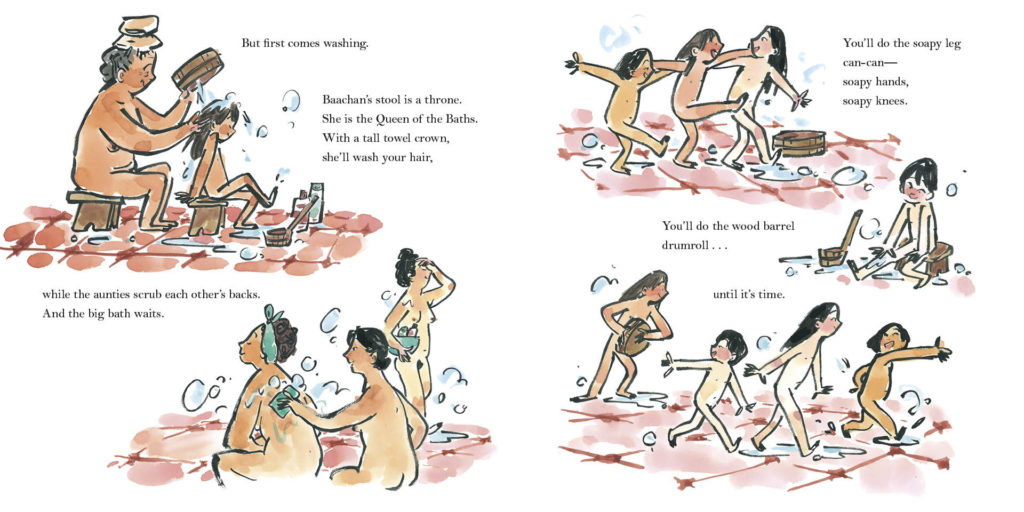

In The Big Bath House, I didn’t set out to deliver any direct or grand message about body positivity but I realize it’s there unapologetically, particularly because of Gracey’s amazing art. I love seeing Asian bodies take up space on the page and seeing Asian women caring for each other. We live in a culture that promotes beauty dogma and body hatred from such a young age so I am always looking for ways to challenge ideas of what beauty is. I want us to embrace and show all the parts of ourselves.

GZ: One of the first questions I asked when I received the manuscript was “Can I draw the people fully nude, front and back?” It felt important to me to show the bodies without having to hide or sneak in ways of censorship. The bath house is such a place of communion and relaxation and having to cover any part of the body felt antithetical to the spirit of it.

As Geeks OUT is an LGBTQ+ website, I’d feel it be remiss not to mention that when it comes to spaces like hot springs and open baths, there’s still much anxiety for many in our community, though some spaces have been becoming better. What are your thoughts on this and how inclusive these spaces can be in general?

KM: Thank you for raising this. It’s so important! The world I wrote about in our book is an old one and it has been a while since I visited Japan. I hope that the onsen and sentō are becoming more hospitable places for LGBTQ+ visitors, especially those who identify as transgender and nonbinary. Bath houses could and should be places of healing for bodies that have borne so much, over centuries and lifetimes. (The history of backlash against queer bathhouses is a whole other issue but maybe not unrelated to the way marginalized people have been denied spaces in which to self-tend, flourish, and practice community sexual health.)

GZ: I try to show and illustrate stories based on lived experiences and memories but also worlds that I want to see and live in myself. The hope is that they give a sense of belonging to those looking for it or give a wider lens to those unfamiliar to it.

I hadn’t known of the The Rainbow Furoproject (mentioned in the second article) but was so happy to see this initiative! Unfortunately in many cases, familiarity comes before inclusion but it gives me a lot of hope that there are many putting in the work to foster safer and inclusive spaces, especially in environments like a bathhouse that are supposed to nurture and heal.

For those curious about the process behind a picture book, how would you describe the process? What goes into writing one and collaborating with an artist to translate that into art?

KM: Writing children’s books, I realize, isn’t just writing words that go with pictures on each page. I need to imagine the entirety of the book as part of the experience of the story. All of the visual elements (images, lettering, endpapers, etc.) are an important part of the narrative and I always want to leave room for the illustrator to do at least half of the telling too. This means I try to pare my words back as much as possible. Sometimes I write brief art notes but I try to do so sparingly because I don’t want to over-direct things. Part of the joy is surrendering to the collaboration.

GZ: I like to let a manuscript sit with me for a bit and let the imagery ruminate before I commit anything to paper. The sketch process changes for each project, I like to do research and find references for objects, environments, (looking up clothes from different years and eras is also a minor obsession). Certain scenes feel concrete to me as soon as they’re sketches out and some are constantly changing, though sometimes you realize that initial sketch was the one that worked the best!

What are some of your favorite elements of writing/drawing?

KM: Leaving things unfinished so the illustrator can come in and work their magic. I like watching the chemistry that occurs when word and picture meet in unexpected ways.

GZ: Being able to create a world that exists beyond yourself, just like Sims but limitless character options.

What advice would you have for aspiring picture book creators?

KM: What I love most about picture books are their outlaw possibilities. I think children’s publishers, or at least the ones I work with, are willing to take risks. I encourage creators to test cultural conventions, marketing expectations, literary prejudices, narrow preconceptions of form and audience. I have always been drawn to work that jumps fences and am happy when my picture books appeal to adults, too.

GZ: Create for yourself, be critical but don’t let that hold you from getting separate eyes on it. Reach out to others (publishing people are extremely nice), take some time away from the work and sometimes the blur becomes clearer when you’re a few steps back.

What’s a question you haven’t been asked yet, but wish you were asked (as well as the answer to that question)?

GZ: What my favorite toppings are for shaved ice in the summer! I’ve been craving it as well as warm humid summers—my favorite toppings are mung bean, chewy glutinous rice and taro balls, sweet stewed peanuts, and barley.

Are there any other projects you are working on and at liberty to speak about?

KM: I just finished a picture book called Kumo, illustrated by Nathalie Dion, about a shy cloud who, one day, is called upon to take the main stage. I also have a picture book coming out next year about cities, both real and imagined. It’s called If You Were a City and it’s illustrated by Francesca Sanna. On the adult side, I am completing a hybrid memoir about plants and family secrets.

GZ: Something with lots and lots of yeowling, howling, furry four legged friends.

What books/authors would you recommend to the readers of Geeks OUT?

KM: I am a huge fan of Shadow Life by Hiromi Goto and Ann Xu. It’s a beautiful and fierce graphic novel about an older queer Asian woman named Kumiko who is being stalked by death. Kumiko is tough and ingenious and the story moves between literary realism and poetic fabulism with hints of Miyazaki and mukashibanashi. But Hiromi makes the story entirely her own. It’s so, so good. And it’s a portrait of aging I’ve seldom, if ever, seen.

GZ: My choice of literature has been a little all over the place as of late, I recently read Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi that I never wanted to end. All of Taro Yashima’s picture books are beautiful and I’ve been attempting to collect them all. I’ve also been finding solace from the cold in a lot of YA romance fiction. Penelope Douglas has been sustaining me and a few friends for the past few months.

0 Comments