CW: Discussion of grief and eating disorders.

Josh Galarza is a writer, printmaker and book artist from Northern Nevada. After a career in Montessori education, he earned a BA in English and BFA in art from the University of Nevada, Reno, where he later taught printmaking. He currently lives in Richmond, VA, where he teaches at Virginia Commonwealth University while completing an MFA in creative writing. His heart’s home will always be the Sonoran Desert, and he is the three-time reigning world champion of extreme trampoline air-drumming, a sport he invented himself.

I had the opportunity to interview Josh, which you can read below.

First of all, welcome to Geeks OUT! Could you tell us a little about yourself?

Alongside being a writer, I’m a visual artist specializing in printmaking and book arts. I’m forever looking for interesting ways to communicate ideas and explore intriguing subject matter, sometimes with words and sometimes with imagery. I was a Montessori teacher for many years, so I’m a lifelong learner. Currently, I’m having the time of my life as a graduate student and creative writing instructor at Virginia Commonwealth University.

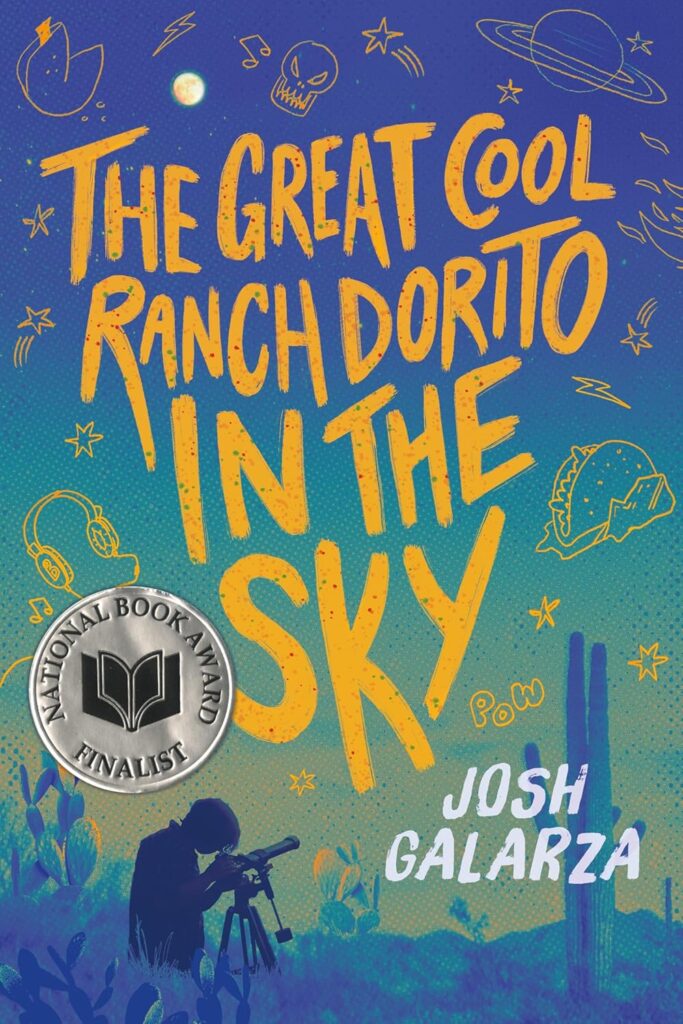

What can you tell us about your debut YA book, The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky? What was the inspiration for this story?

I often describe The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky as a fun book about grief. While I set out to tackle difficult subject matter—including ways disordered eating affects boys—I was also determined to infuse the book with humor, lightness, and a healthy dose of boyish immaturity. At his core, the protagonist, Brett, is a creative, fun-loving kid, so while he’s going through a really tough time, struggling with fear and grief because of his mother’s terminal cancer diagnosis, it was important to me that readers be able to buy into the idea, even from page one, that he could find a way toward healing.

The book was inspired by a spell of grief in my own life, which led me to therapy, which led me to treatment for an eating disorder I’d been suffering from for many years. Boys aren’t socialized to talk about their anxieties at all, let alone anxieties about their bodies, so it’s really easy for destructive behaviors and illnesses like eating disorders to take hold without them even knowing it’s happening. I recognized an opportunity. In writing a book that might help me through my own healing, I could raise awareness and normalize vulnerability for young male readers. To participate in taking down diet-culture, we first must see it at work in our own lives. So the book is as much about consciousness-raising as it is about anything else.

As a writer, what drew you to the art of storytelling, especially young adult fiction?

I got into Montessori at a really young age, so I’d already been teaching several years when I decided to begin slowly taking classes toward a BA at the age of 26. My first class was in English composition. I had no idea I had any talent or that my writing might be special, so when my professor called me into her office to discuss my essays, I was afraid I’d done something wrong! Instead, my professor wondered if I had any aspirations as a writer. Suddenly I wondered, too. I immediately enrolled in classes with a local legend, Marilee Swirczek, who quickly took me under her wing. For many years, I thought I was meant to write literary fiction for adults. My challenging subject matter and artistic approach certainly suggested as much. But it wasn’t until this sixteen-year-old kid popped into my head and I began writing his story—what eventually became The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky—that my sensibilities, talent, and execution finally fell fully into place. I was always meant for YA. My adult protagonists were always coming of age in some way, self-actualizing. I just couldn’t see it. I often joke that I had to get “old” to write for young people. Twentysomething me took himself way too seriously, and I needed the perspective distance brings to finally become the writer I was meant to be.

How would you describe your writing process?

A hot mess! But seriously, like most literary writers, I’m a pantser, not a planner. I’m not the most disciplined about daily writing time or studio time—I’m just as likely to write for hours propped up in bed as I am to sit at a desk during normal working hours. Sometimes the inspiration strikes at a convenient time and sometimes it doesn’t, which frustrates the toxic overachieving perfectionist in me. That side of me would really love for my writing practice to look neat, tidy, and professional. This disconnect is likely why I work best under deadline. I often need an external motivator to wrangle the internal procrastinator who might just as soon binge-watch TV. There are some signs, however, that I’m coming along in my quest toward a more professional approach. For instance, I was recently shocked and really proud when I managed to write a detailed outline for my next book proposal. Despite my willingness to let the art guide me as I write, I have learned a great deal from writing several manuscripts over fifteen years. I have strong instincts and was lucky to get a super strong education in craft (rarer than one might guess), so when crunch time comes, I know I’m capable of whipping myself into shape.

What are some of your favorite elements of writing? What do you consider some of the most frustrating and/or difficult?

I think my favorite element is voice, primarily because it acts as a writer’s fingerprint—no two voices are quite the same. Plus, voice is challenging. It’s hard to pin down how voice works from a craft perspective. Teaching elements like setting or characterization is easy—or at least there are plenty of well-established approaches to do so. But voice is the mysterious sum of a character’s perspective and idiolect, so the prose itself is working in conjunction with the countless facets of that character’s entire makeup, not to mention the entire makeup of the writer himself, as nebulous, layered, and far-reaching as a person’s psychology. And it seems one either has a voice or he doesn’t. I’ve found as an educator that you can develop a writer’s voice when it already exists, but I have yet to figure out a way to actually teach a student to write with a recognizable voice. Maybe there are educators out there who can do it, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen it.

Maybe the most frustrating element for me is setting. Perhaps because I’m such a voice writer, all my work is extremely character driven. My storytelling, therefore, is often cerebral. I can happily spend all the time in the world in a character’s head, but I’ve had to work really hard to consistently ground my writing in time and space. The trick to that, of course, is to write setting that reveals character, contributes to tone or mood, or comments on theme. In this way, setting becomes vital rather than obligatory. If the setting just exists to ground a scene? I know I need to do better.

Many authors would say one of the most challenging parts of writing a book is finishing one. What strategies would you say helped you accomplish this?

External deadlines are a lifesaver for me. With this book, I had to turn in pages to my writing workshops at the University of Nevada, Reno twice a semester, so while I could focus on my visual art or other endeavors for weeks at a time, whenever a deadline rolled around, I’d buckle down and get several chapters written. And those lulls are great for working out story problems since the gears are always turning in my head, even if words aren’t being committed to paper.

I absolutely hate to miss out on meaningful critique—critique is one of the greatest gifts a writer can receive, and many are not so lucky to have the easy access I do—so I never took those opportunities for granted and always tried to turn in as many pages as were allowed. Before I was deeply entrenched in academic writing environments, I was a founding member of a critique group with several friends. We met once a week, and you can bet I wasn’t going to show up emptyhanded when I knew my buddies were going to show off their awesome new pages. We were never competitive—competitiveness is useless in publishing and a sure sign of insecurity—but we did motivate one another because none among us wanted to be the guy who wasn’t making good on his dreams. The not-so-hidden tip in here for aspiring writers is this: writing is not a solitary activity—or at least it shouldn’t be.

Aside from your work, what are some things you would want others to know about you?

Few things on earth bring me as much joy as karaoke. I can’t sing men’s voices well, but I’m a master of the divas. If you need a killer rendition of a Whitney Houston or a Celine Dion, I’m your man.

What’s a question you haven’t been asked yet but that you wish you were asked (as well as the answer to that question)?

Brett has a real throwback sensibility regarding the media he loves, including his taste in music, films, and even professional wrestlers. What guided that impulse?

Thanks for asking! So often you hear rumblings (and grumblings) that many people who write YA are out of touch with young readers. Some think you’re getting YA wrong if you’re not drowning readers in the latest neologisms, technology, and pop culture interests. Some writers fear their characters won’t seem authentic if they don’t overtly illustrate everything it means to be a teen in this particular moment, but I have never shared that fear. There are plenty of commonalities (if not universalities) to the experience of coming of age, and young people have more access than ever to all the media that came before them. I remember a girl in junior high (shoutout to Janelle Timmons!) who seemed like the coolest kid in school because the bands she listened to were before our time. It’s not strange to think that kids will explore and find much to love beyond the media we’re currently feeding them. I think when it comes to writing authentic teen characters—and especially characters who will stand the test of time—success has little to do with throwing words like “rizz” or “fit” into the story but rather knowing who this kid is and why he loves what he loves. Authenticity is never about the trappings of a character but about the recognizable expression of a character’s humanity.

What advice might you have to give for aspiring writers?

Pay your dues. Writers who excel treat the artform and their writer’s practice with the same respect they would any other professional endeavor. Invest in your writer’s education. Buy into the idea that to be worthy of having an editor someday you should develop the skills to be an editor. Most importantly, we learn much more from critiquing the work of others than we ever could from being critiqued, so build a community of writers around you with an enthusiasm for the hard work of not just writing but workshopping.

Are there any other projects you are working on and at liberty to speak about?

I’m drafting my next YA novel, a wacky yet challenging mashup of musical tropes and action film tropes. Much like The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky, the book deals with heavy themes—in this case internalized homophobia, conversion therapy, and machismo culture—but once again I’m striving to write an ultimately hopeful, empowering story that illustrates pathways through trauma and invites readers to celebrate and respect themselves more fully.

Finally, LGBTQ+ books/authors would you recommend to the readers of Geeks OUT?

My current obsessions are The Deviant’s War, a work of historical nonfiction by Eric Cervini that explores the roots of the fight for queer rights long before Stonewall, and Disorderly Men, a work of literary fiction by Edward Cahill that follows the experiences of three gay men whose lives intersect during the time explored in Cervini’s book. I’m very much the creative researcher, and I’m always on the lookout for the next aspect of queer history I want to dive into. As illustrated here, my research practice nearly always involves a great deal of fiction and nonfiction, and I’m very much an autodidact, my interests driven by a desire to continually grow as a human being so that my artistic contributions to the world will be as mindful, ethical, and well-informed as possible. There are a lot of ways a writer gains authority, but for me it’s always, always, always about putting in the work.

0 Comments