by Michele Kirichanskaya | Aug 11, 2023 | Blog

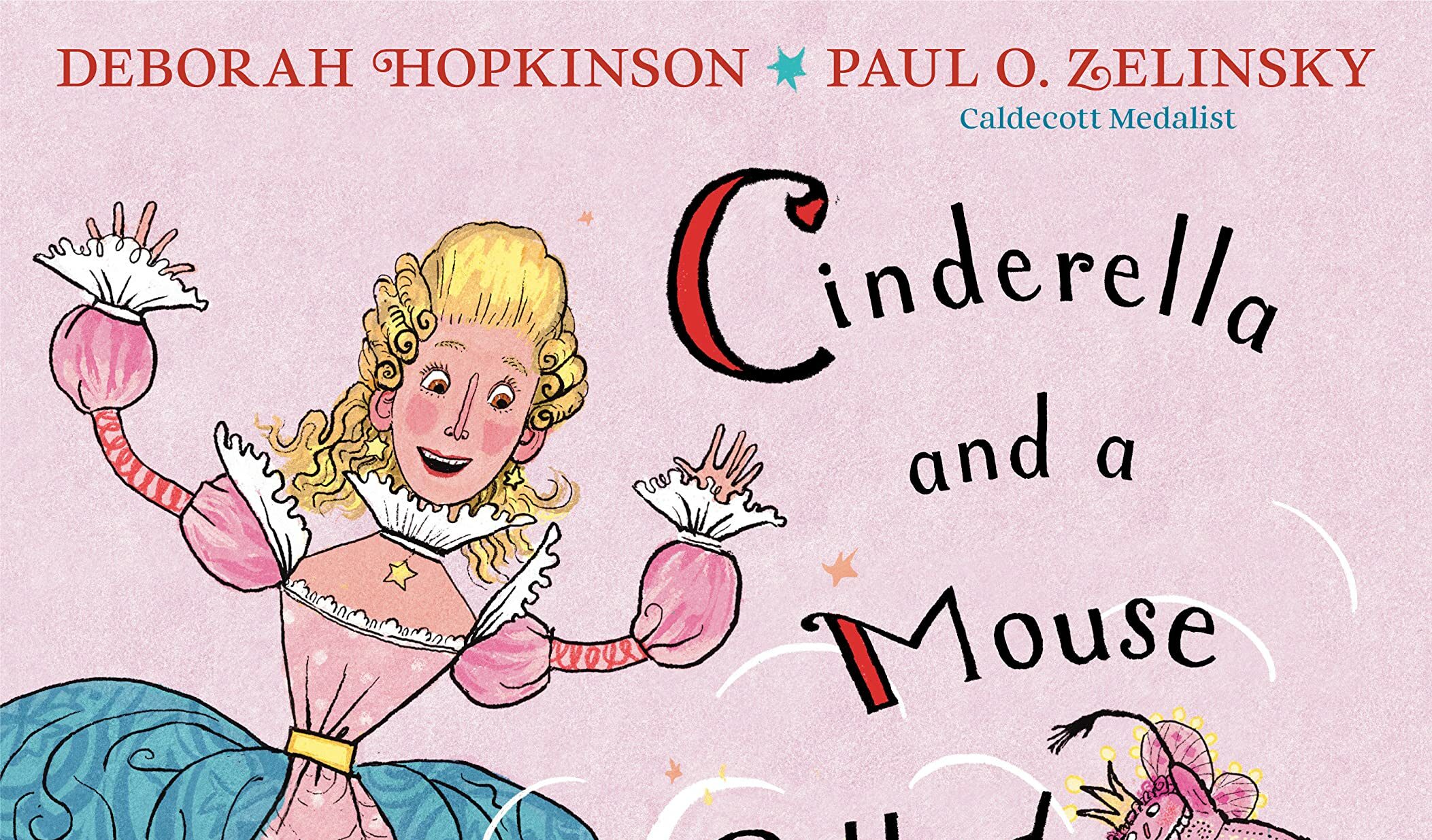

Deborah Hopkinson is the author of many highly acclaimed picture books, including A Letter to My Teacher, which received two starred reviews, and the modern classic Sweet Clara and the Freedom Quilt, which the New York Times called “inspiring.” Her other...

by Michele Kirichanskaya | Aug 8, 2023 | Blog

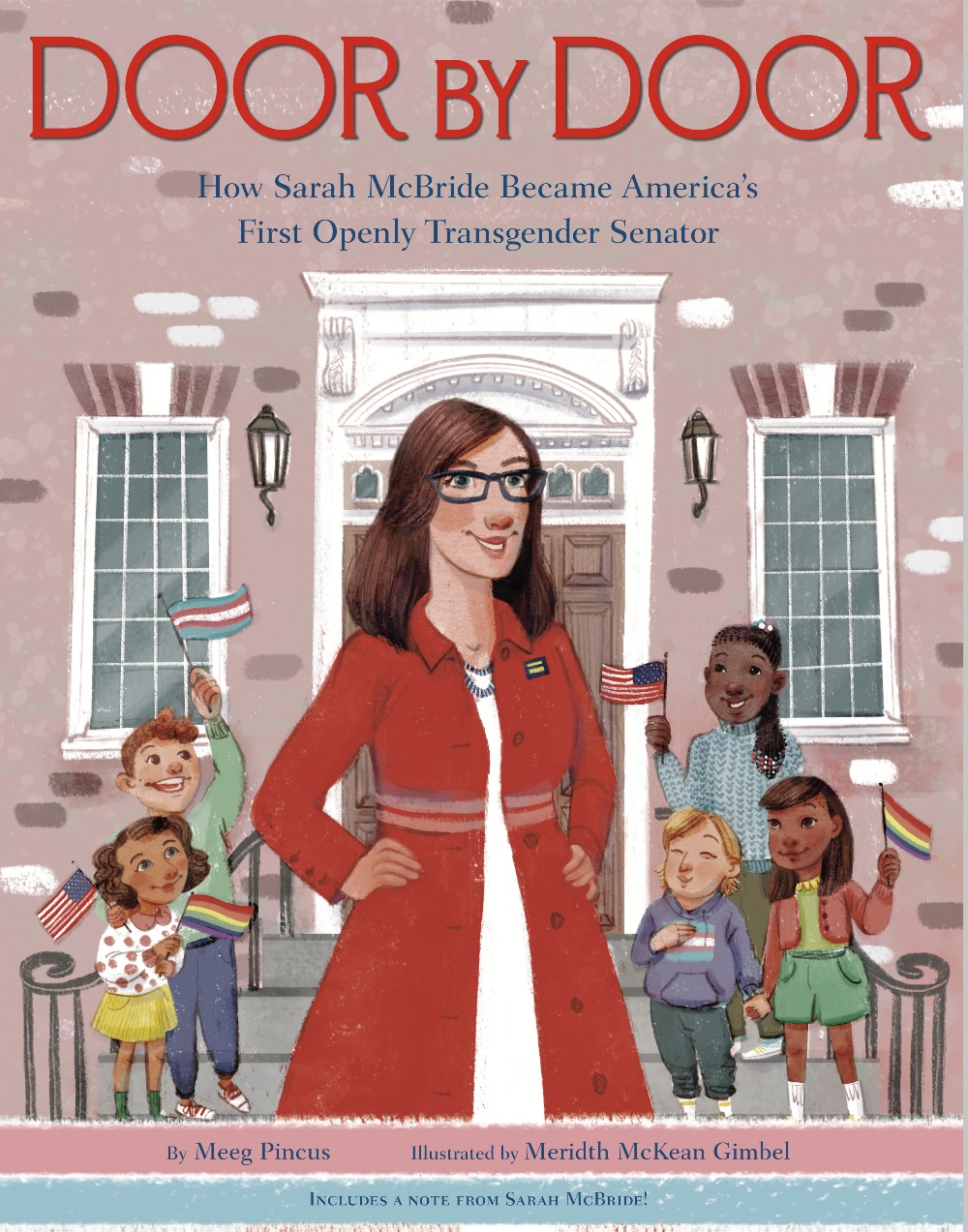

Meeg Pincus (she/her), M.A., is the author of 26 picture books in the trade and school/library markets. She’s been a nonfiction writer, editor, educator & diverse books advocate for over 25 years. She lives, writes, sings & homeschools with her family in...

by Michele Kirichanskaya | Aug 7, 2023 | Blog

Carlyn Greenwald writes romantic and thrilling page-turners for teens and adults. A film school graduate and former Hollywood lackey, she now works in publishing. She resides in Los Angeles, mourning the loss of ArcLight Cinemas and soaking in the sun with her dogs....

by Michele Kirichanskaya | Aug 5, 2023 | Blog

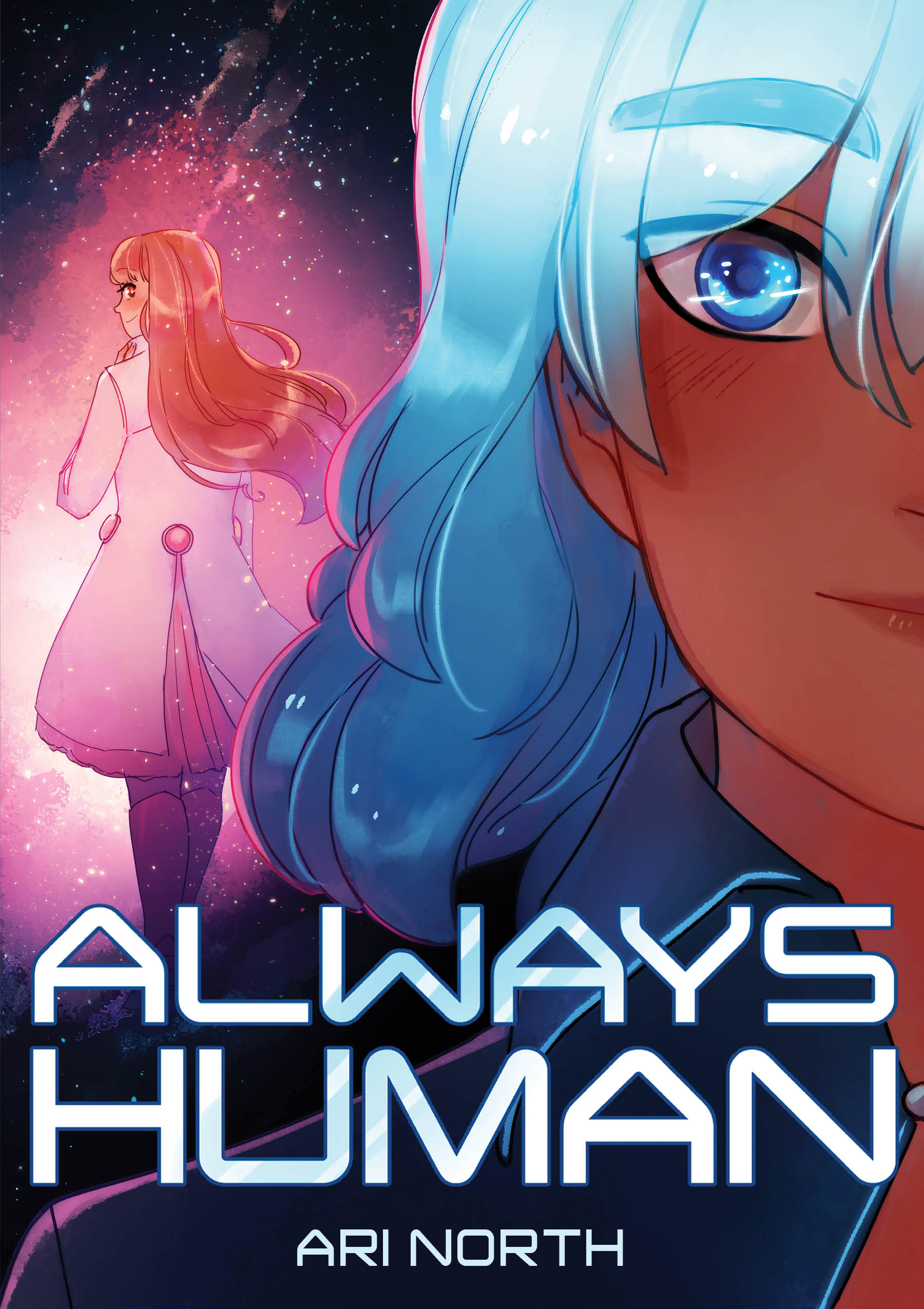

Ari North is a queer cartoonist who believes an entertaining story should also be full of diversity and inclusion. As a writer, artist and musician, she wrote, drew and composed the story and music for Always Human, a complete romance/sci-fi webcomic about two queer...

by Michele Kirichanskaya | Aug 3, 2023 | Blog

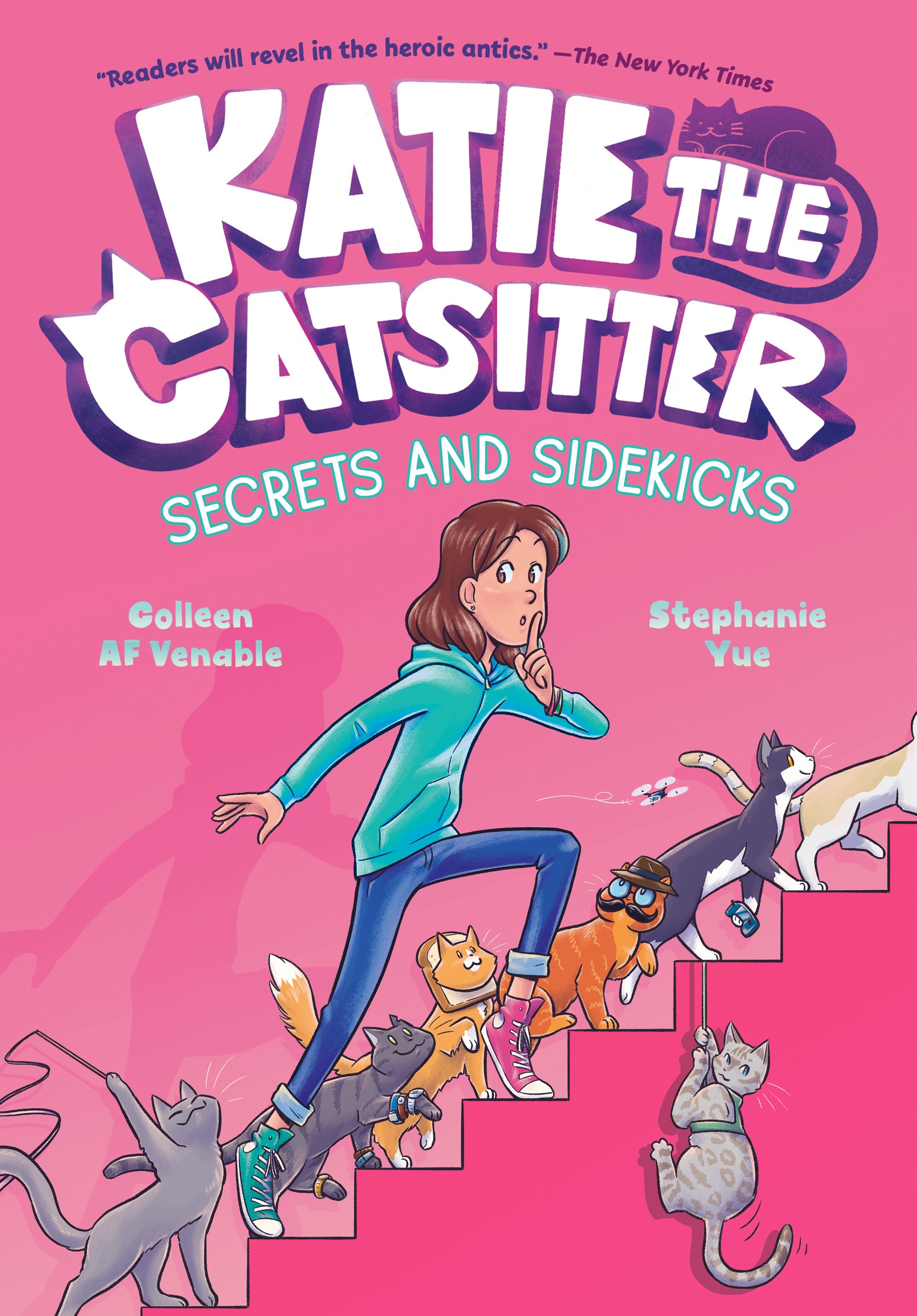

Colleen AF Venable is the author of indie bestseller Katie the Catsitter graphic novel series with Stephanie Yue, as well as the National Book Award Longlisted Kiss Number 8, a graphic novel co-created with Ellen T. Crenshaw. Her other books include Mervin the Sloth...