by Daniel Stalter | Jun 7, 2019 | Blog

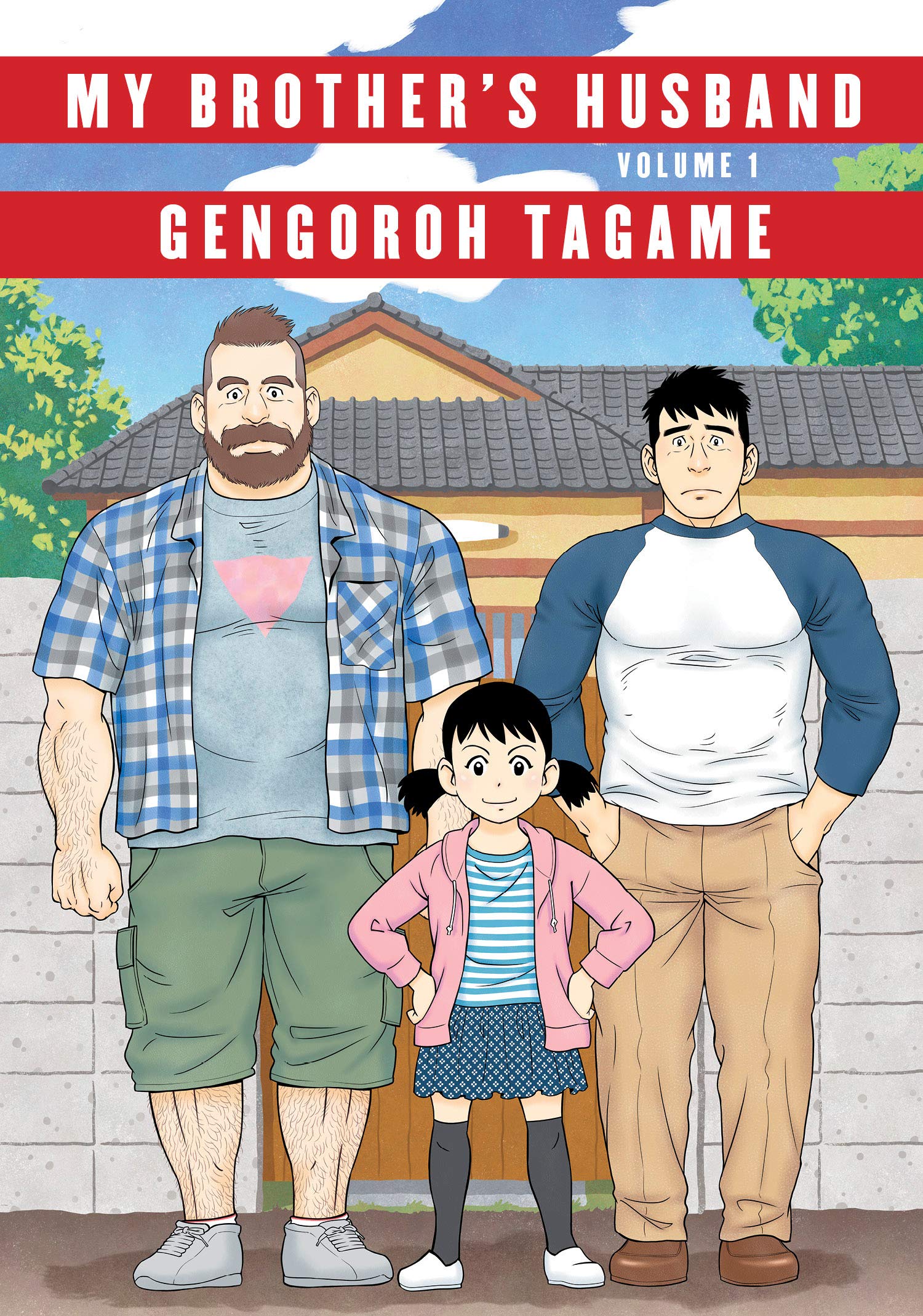

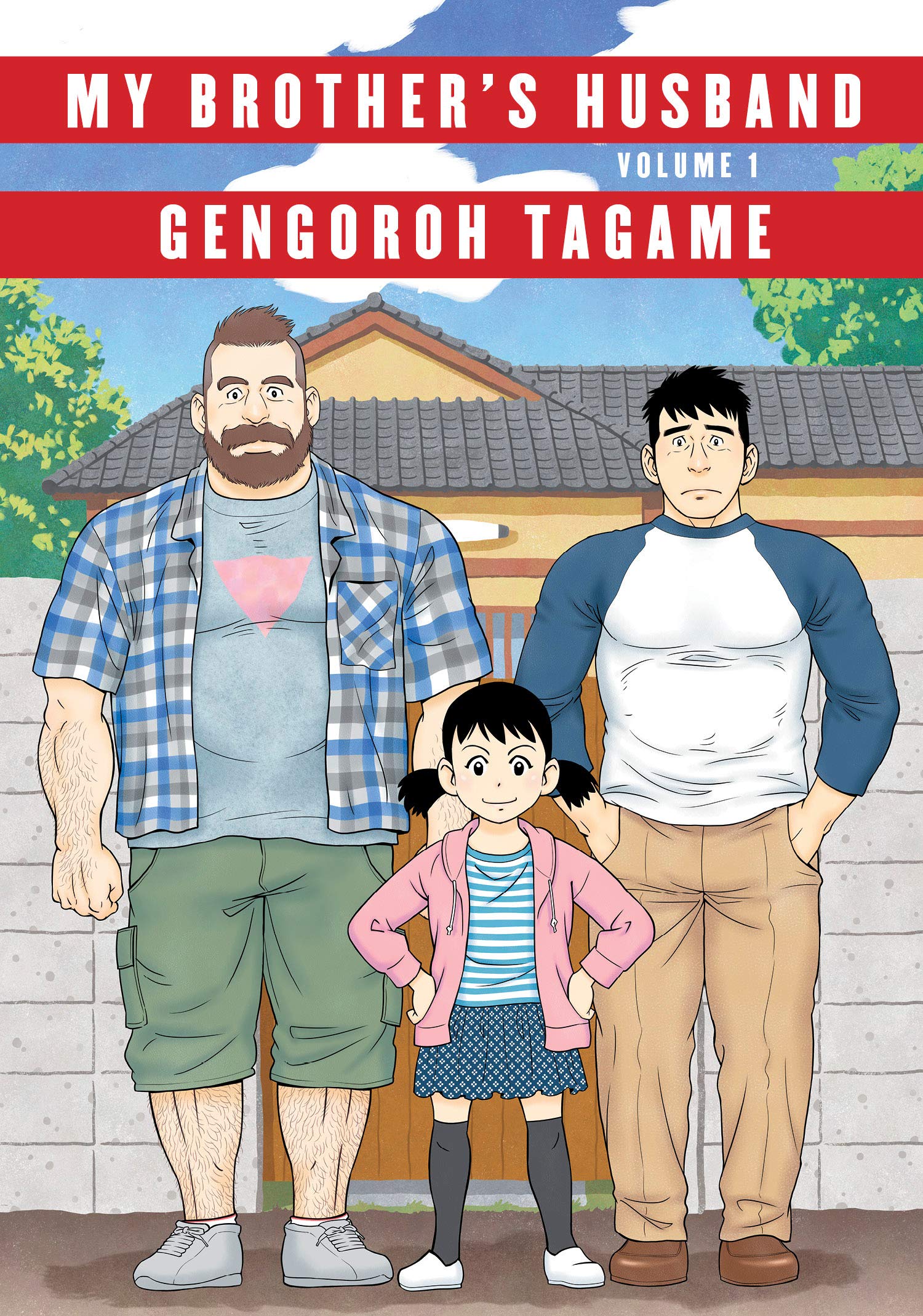

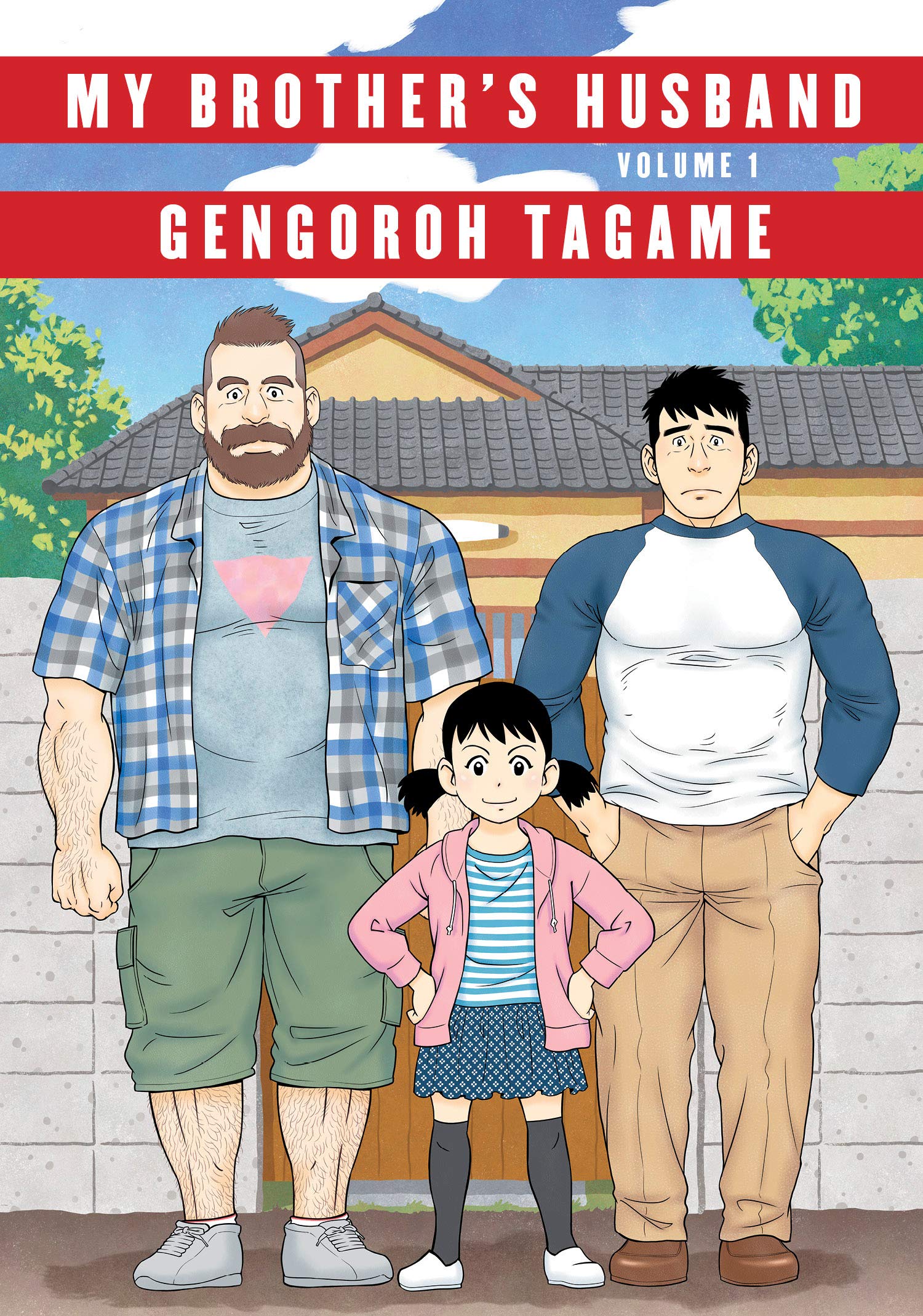

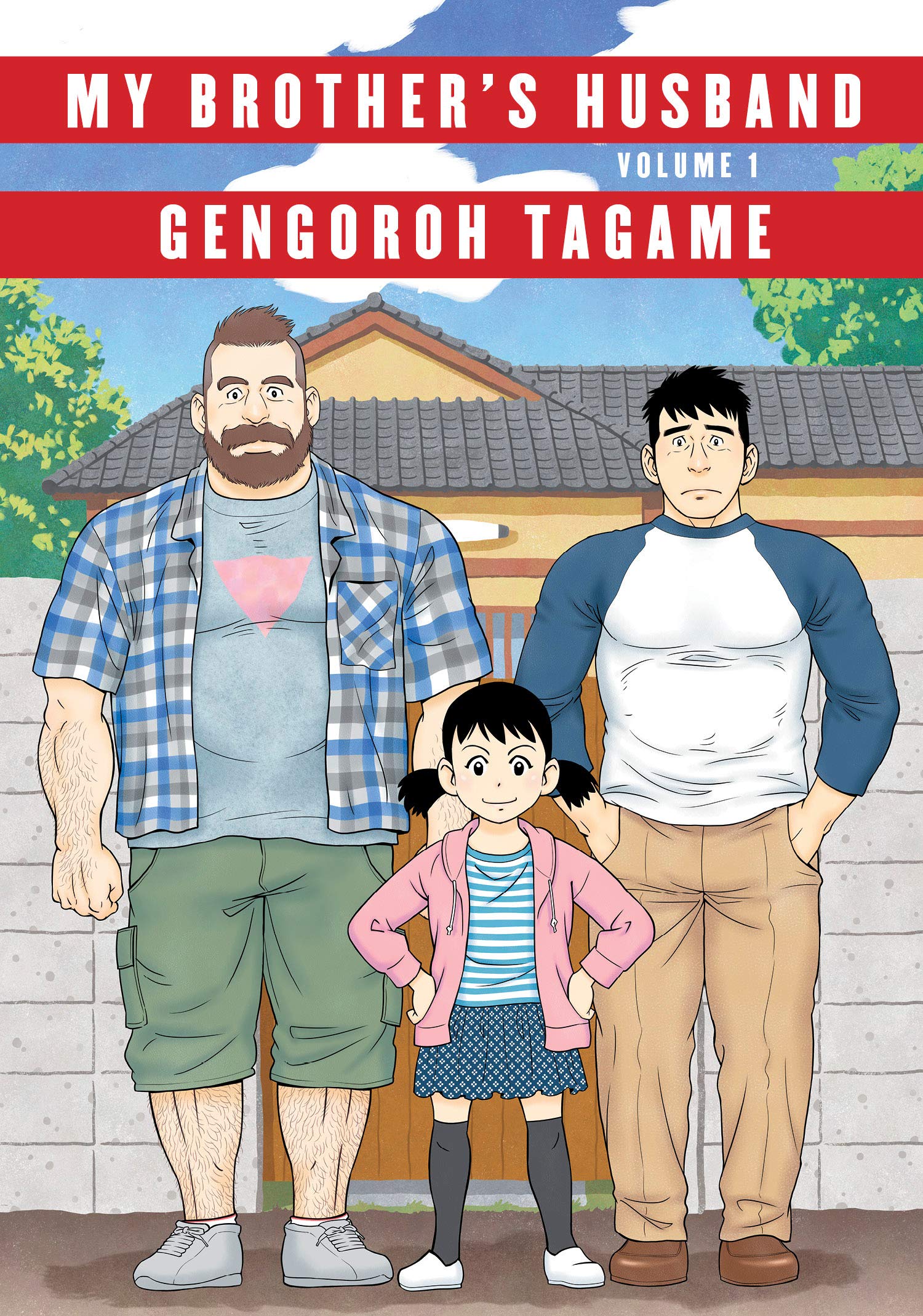

My Brother’s Husband is an all-ages manga series by Gengoroh Tagame. It was recently collected into two volumes by Pantheon Books, the first of which won the 2018 Eisner Award for Best U.S. Edition of International Material—Asia. It tells a powerful and heartwarming...

by Michele Kirichanskaya | Jun 29, 2018 | Blog

Erica Friedman is the Founder of Yuricon, a celebration of yuri (lesbian-themed) anime and manga held in New Jersey from 2003 to 2007 that now exists as an online entity, as well as the founder of ALC Publishing. She describes herself as an LGBTQ and Geek Marketing...