by Michele Kirichanskaya | Jan 19, 2022 | Blog

Aden Polydoros grew up in Illinois and Arizona, and has a bachelor’s degree in English from Northern Arizona University. When he isn’t writing, he enjoys going to antique fairs and flea markets. His debut novel, The City Beautiful, is available now. He can be found on...

by Michele Kirichanskaya | Jan 15, 2022 | Blog

Cody Daigle-Orians (he/they) is an asexual writer and educator living in Hartford, Connecticut. He is a member of The Ace and Aro Advocacy Project, a Washington, DC-based organization providing resources on asexuality and romanticism to the public. And he is the...

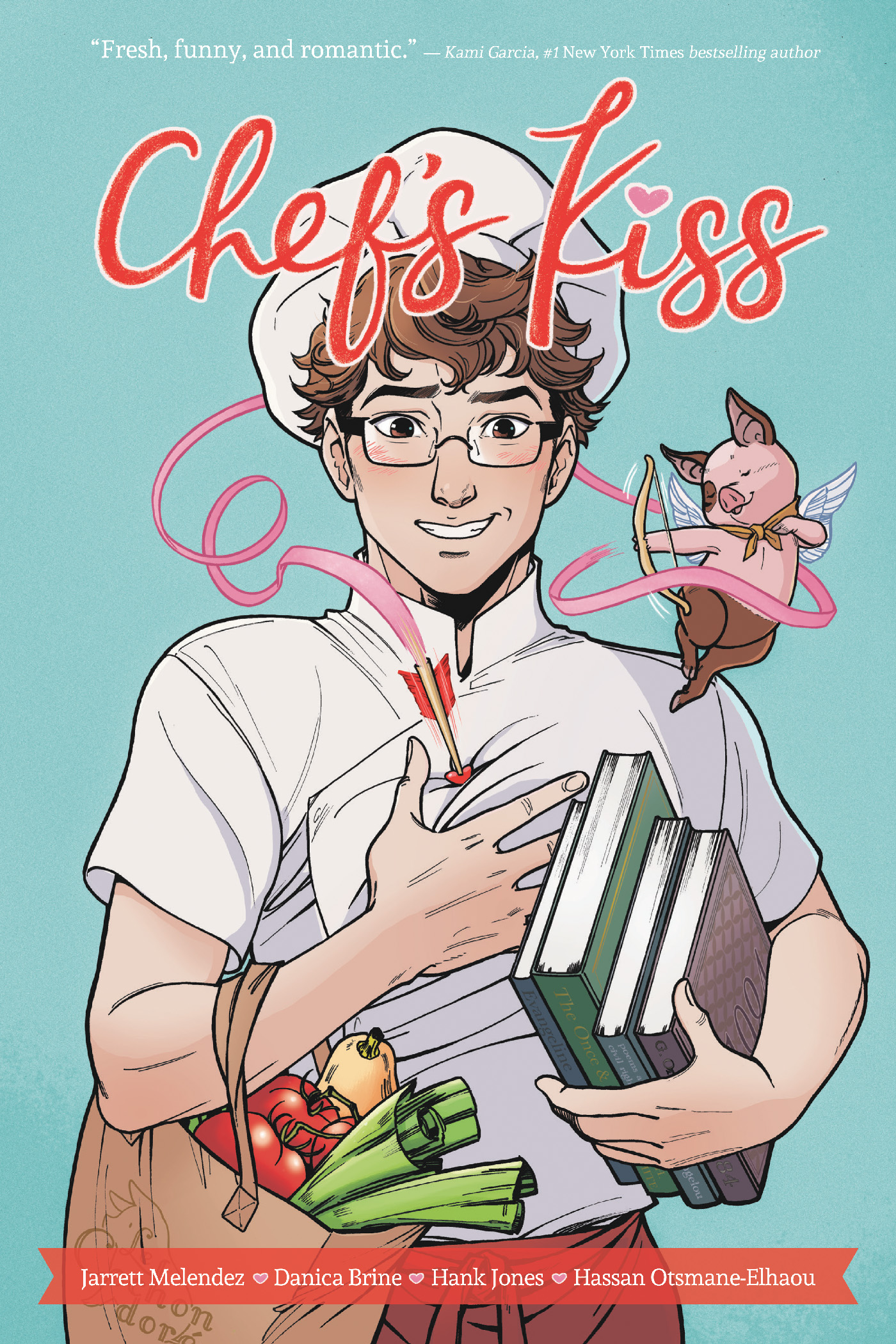

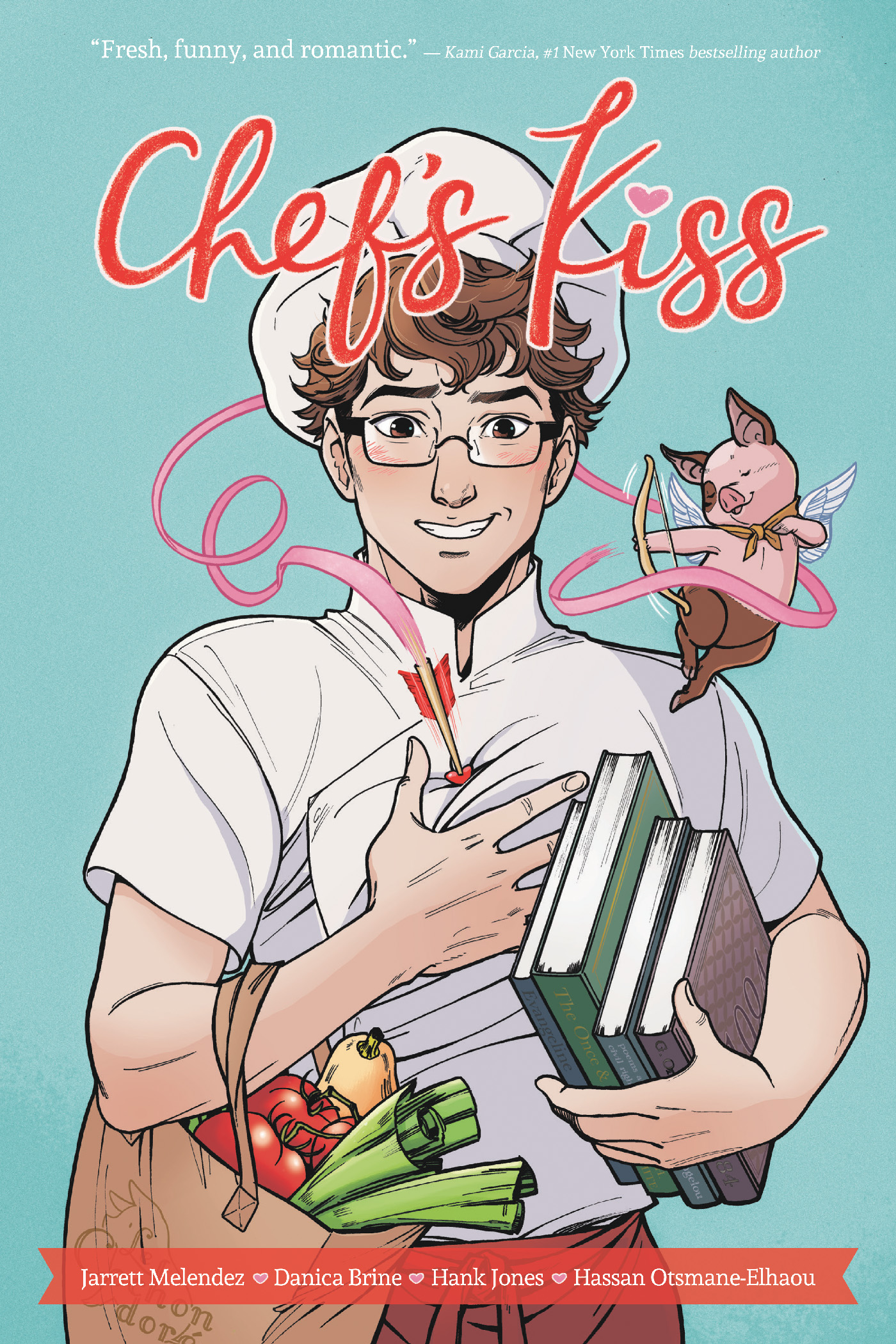

by Michele Kirichanskaya | Jan 12, 2022 | Blog

Jarrett Melendez grew up on the mean, deer-infested streets of Bucksport, Maine. A longtime fan of food and cooking, Jarrett has spent a lot of his time in kitchens, oftentimes as a paid professional! Jarrett is a regular contributor to Bon Appetit and Food52, and is...

by Michele Kirichanskaya | Jan 7, 2022 | Blog

Born and raised in the DC Metro Area, and currently living in Brooklyn, Kosoko Jackson is a digital media strategist for non-profit organizations; which enables his Twitter obsession. Occasionally, his personal essays have been featured on Medium, Thought Catalog, and...

by Michele Kirichanskaya | Jan 5, 2022 | Blog

Alechia Dow is a former librarian and pastry chef living abroad with her partner in Germany. When she’s not writing, you can find her having epic dance parties with her daughter, baking, reading or taking teeny adventures around Europe. I had the opportunity to...

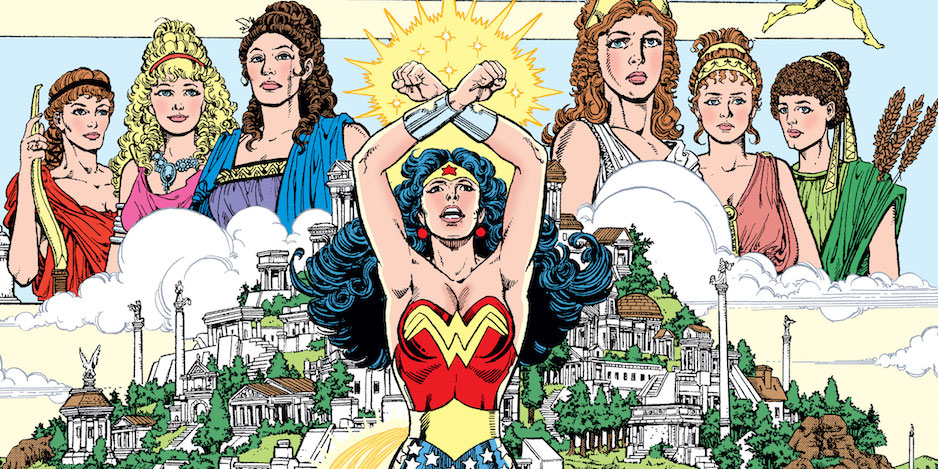

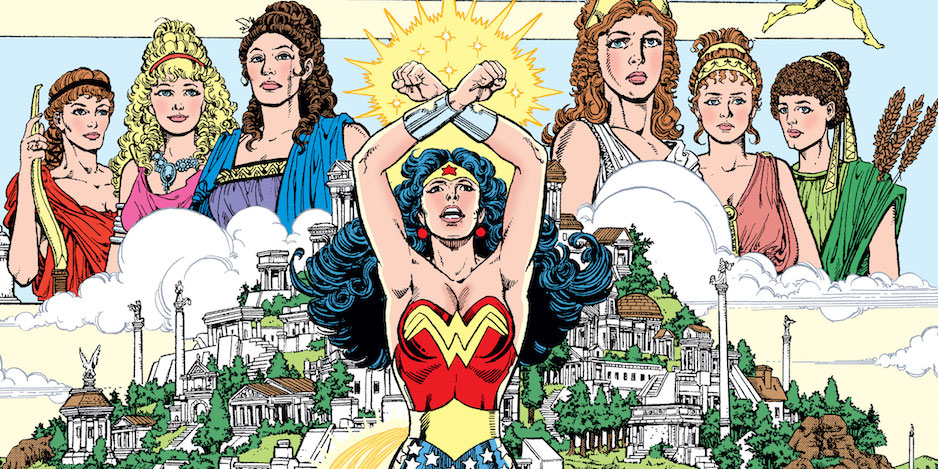

by Chris Allo | Jan 3, 2022 | Blog

All-Star Comics 8, Sensation Comics 1 DC Comics Wonder Woman was co-created by William Moulton Marston and H.G. Peter. She first appeared in All-Start Comics #8 in 1941. Some of us know Wonder Woman from her origins in comic books. Stories crafted by the likes of...